Yasemin Copur-Gencturk knows the secret ingredient to optimizing K–12 math-teacher education.

She first encountered it in Çelebi Aslan, her elementary school teacher in Kayseri, Turkey. What made Aslan extraordinary wasn’t that he loved his students. It’s that he loved math. If you could propagate this secret ingredient, replicate it … well, then no math-learner need ever be left behind.

“I loved Mr. Aslan so much,” Copur-Gencturk says, with a musical laugh.

To his mind, math should be ice cream and problem-solving a treat.

“If we did something really well as a class, our prize was a hard math problem,” she recalls.

Inspiring a love for math is the vision driving Copur-Gencturk.

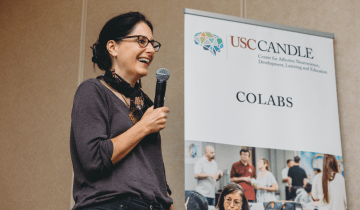

Since joining USC Rossier’s faculty in 2016, the 37-year-old assistant professor has been making her mark. Last year alone, she earned four federal research grants worth nearly $5 million, including the prestigious NSF CAREER grant, the National Science Foundation’s highest accolade for young researchers.

She believes math-love is contagious, passed down from teacher to student. Conversely, teachers who dislike math pass on their antipathy.

“The reason we are struggling so much in math education is that most people who are really good at math are not willing to be teachers,” Copur-Gencturk says. “And those rare teachers who do love math are not ending up teaching math, especially not in elementary school.”

With math scores for fourth- and eighth-graders in the most recent National Assessment of Educational Progress showing no improvement since 2015, Copur-Gencturk believes she’s found a solution: Introduce ordinary teachers to the beauty of math.

“If kids saw math the way that I see it, they would love it,” she says. “It’s so beautiful because it’s so logical. As long as you notice the pattern, you can arrive at important conclusions all on your own.”

Copur-Gencturk believes that to understand math, the learner must first concentrate on meaning—not focus on problem-solving steps. Right now, the pedagogy goes in the opposite direction.

“We teach kids to memorize things and not to understand why, conceptually,” she says. “It’s easier to learn procedurally when you are younger, because the procedures are very straightforward. But if you know the meaning behind those steps, it gives you a very special power.”

Copur-Gencturk was the second of six children raised in a working-class Turkish home where education was not a priority. Neither parent had attended college; her mom worked in the home, and her father struggled to pay the bills on a civil servant’s salary.

But Copur-Gencturk was both academically gifted and driven. At 5, she started dressing herself in her older sister’s outgrown uniform and demanding to go to school with her. Indulged by their mother, Copur-Gencturk “audited” the fourth grade until her embarrassed sister put a stop to it.

A math prodigy, Copur-Gencturk absorbed concepts quickly and spent the remaining class period “waiting, doing nothing, doodling.” To make matters worse, she was stuck in vocational schools where STEM education was watered down. Her parents didn’t know how to navigate Turkey’s tiered educational system and couldn’t afford the expensive after-school and weekend prep academies everyone attended before testing into Turkey’s elite “science high schools.”

Copur-Gencturk dreamed of attending a top-ranked college and becoming a mathematician, but instead experienced how first-generation, economically disadvantaged students get left behind competing against more privileged peers.

“We were expected to run to the same finish line, but I felt like I had weights on my feet,” she says. “Senior year, I cried every day, knowing I was not learning many things that would be assessed on the nationwide college entrance exam.”

Against all odds, she did well enough to be admitted to a respectable university in the capital city of Ankara. Then came trouble around her headscarf.

Copur-Gencturk comes from a religious family and covers her hair. The year she started college, Turkey’s stridently secular government implemented a law banning headscarves from university classrooms.

The law, inconsistently enforced, made Copur-Gencturk’s college years a tactical nightmare. An incremental disciplinary system—first time, warning; second time, suspension; third time, expulsion—forced Copur-Gencturk to walk a tightrope.

“Oh, my goodness, it was bad, very bad,” she recalls. “My first year, especially, I felt I was in the crossfire. I felt pressure from both sides, and many girls were quitting school.”

Sometimes she removed the headscarf and wore a wig. Sometimes she took her chances, hiding in the back row of class. Because she was so gifted in math, many of her professors looked the other way.

She eventually devised a compromise strategy: She would wear her headscarf until a warning was issued, then stop attending that class to avoid triggering further disciplinary action. She kept up with those classes through independent study and only showed up for exams.

Thinking about that period of her life still brings tears. It’s a testament to her talent and tenacity that Copur-Gencturk graduated from Hacettepe University summa cum laude.

She still dreamed of becoming a mathematician, cracking a famous unsolved problem and winning a Fields Medal—“the Nobel Prize” for mathematicians under 40. The next step required coming to America for her PhD. But admission to a U.S. graduate school seemed unattainable: Application fees alone were prohibitive, and Copur-Gencturk spoke no English. She’d need to take expensive language classes before sitting for the TOEFL.

Discouraged, Copur-Gencturk went to work as a high school math teacher in Ankara, but soon learned of a scholarship opportunity through the Ministry of Education. The grant covered everything—language academy, tuition, fees, living expenses—but she would have to earn a degree in math education, not theoretical math.

“I was thinking I could find a way to move into the PhD in math program once I arrived,” says Copur-Gencturk, who was admitted to the University of Illinois at Urbana–Champaign. “But when I started taking courses in math education, I was inspired. I didn’t realize there were people doing research in this—people motivated to improve inequity.

“I remember how desperate I was, how many times I lost hope, all the things that had hurt me. I still cry when I think about my undergraduate years,” she adds. “That’s why I’m so motivated to make changes in the educational system and remove discrimination—to make sure that no one, regardless of their gender, color, race, religion or anything else, is treated differently.”

The idea of helping math students through research “brought meaning to my life and changed my mind about what I wanted to do,” she says. “It became so important to me that I said, ‘Bye-bye dreams of being a great mathematician and winning the Fields Medal.’”

She earned her doctoral degree in math education in 2012 from the University of Illinois. She also holds master’s degrees in statistics and secondary education. Before joining the USC Rossier faculty, Copur-Gencturk was an assistant professor at the University of Houston and a postdoc at Rice University.

Around the same time she was falling in love with math education, Copur-Gencturk also fell in love with Bora Gencturk, a civil engineering student at Illinois. They met at Friday prayers on campus. Today, they are married, and he is on the USC Viterbi faculty. The family lives in Palos Verdes, Calif., where their daughter, Verda, attends first grade—but won’t accept any math tutoring from her expert mother.

“It’s driving me nuts,” Copur-Gencturk says with a grin. “She says, ‘Mommy, you’re not my teacher!’”

Given all the hurdles she faced, what made it possible for Copur-Gencturk to beat the odds and thrive academically? Certainly, being math-gifted and stubborn helped. But it came down to one big thing: the skill and encouragement of her math teachers.

And that’s why, today, she focuses her energies on the transmission of those qualities to the next generation of teachers.

Copur-Gencturk’s research focuses on teacher knowledge, teaching practices and teacher development, and how these areas relate to student learning. She drills down on the mathematical knowledge teachers need to promote student learning in diverse classrooms, paying special attention to innovative learning opportunities for teachers. She also studies the dynamics between teacher perceptions of students’ learning and actual student performance.

“People like me who come from underprivileged families value their teachers’ opinions a lot,” she says. “My teachers either shaped or ruined my confidence and influenced my beliefs about what I could and could not do.

“If I can help one teacher, how many kids am I saving?” she adds. “It’s not just about how much teachers know about math; it’s about the hope they give.”

Q&A

How do you feel about math homework?

I’m against homework, because it increases the achievement gap, depending on how much support kids get from their parents. More importantly, it doesn’t advance the purpose of math education, which is to have students grasp concepts. I was always a top student in math, and I never did my homework.

Is there such a thing as a “math brain”?

There will always be geniuses. When we see remarkably gifted ice skaters or gymnasts, we don’t say, “Anyone who works very hard will get those results.” That’s unrealistic. But the impact of giftedness on success is not as big as people think. Anyone can learn and excel in math. I’ve seen over and over again how people—with hard work—can achieve things so-called geniuses cannot imagine. It’s about the effort.

What’s your advice for math teachers and engaged parents?

Probe for meaning. Ask kids to explain why they solved a problem the way they did and how they arrived at the answer. Don’t use tricks or catchy phrases. The right way to teach a child to borrow in subtraction is to explain the logic of base 10, not to talk about “borrowing milk from the neighbor.”

Should parents hire math tutors to supplement school instruction?

If the tutor is teaching meaning, go for it; if the tutor is teaching to the test, no. Time is valuable. I don’t want kids to spend time preparing for a single exam without seeing any relevance to what they have learned. I took a differential equations course when I was in college. For the final, we were not allowed to use calculators. We were required to do everything by hand and memorize all these weird rules. After winter break, people were still talking about that final. I had gotten an A in the class. And guess what: I didn’t remember a thing I’d learned by rote memorization. It was gone.

Many high schoolers hit a wall with advanced math. Should they all be required to take it?

It’s about teaching. If students are hitting a wall, it’s probably because the math concepts aren’t being taught appropriately. Mathematical reasoning is very simple. What gets complex is expanding that reasoning to different domains and applications. I’m not going to say calculus is unnecessary, but high school students have to learn statistics, too.

What about math and music? Should teachers play Bach during class?

Some experts encourage that, hoping it helps kids see how math is connected to different fields or “real life.” I think that’s a good thing. Anything that includes a pattern is related to math—of course, music is very pattern-based. You don’t need music to teach math. But I want kids to see the logic in math by itself. There is beauty in math, and math is everywhere. It’s not like any other subject. All the dots get connected.

RESEARCH

In March 2018, Yasemin Copur-Gencturk won the coveted NSF CAREER Award—the agency’s highest distinction given to junior faculty. It was the first of four federal grants she earned during 2018, worth nearly $5 million. Building on a stream of research supported by the USC-based Joan Herman & Richard Rasiej Mathematics Initiative, three of Copur-Gencturk’s federally funded studies focus on math teachers and pedagogical content knowledge. The fourth, led by a USC Viterbi civil engineer, investigates virtual-reality teaching environments to improve human–robot collaborations.

Memories of a Mathematician

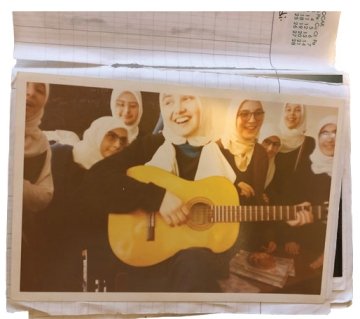

“I don’t have many pictures with me, but these are the ones I’ve kept,” says USC Rossier Assistant Professor of Education Yasemin Copur-Gencturk of these images, which she saves in her math notebook.

|

|