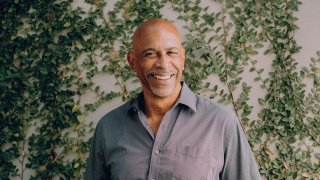

Pedro A. Noguera is not afraid to speak his mind. He attributes this candor and gumption to his mother, a Jehovah’s Witness who would take him and his siblings with her preaching, door-to-door.

To knock on strangers’ doors, “you have to be unafraid,” Noguera says. And while the hardest part was living in constant fear that “a kid from school would see me,” the experience helped him develop a deep sense of conviction about his core values and beliefs.

He left the religion around age 15, but “the idea of standing up for what you believe in was already in me and has stuck with me ever since.”

The standing up has been less literal this year, as the COVID-19 pandemic has shifted most interactions to in front of a computer. But the assertiveness remains, perhaps at odds with the calm of what has become Noguera’s signature Zoom background: a world map cast in earth tones, green fronds of potted palms flanking either side of him.

On July 1, Noguera started his new role as the Emery Stoops and Joyce King Stoops Dean of the USC Rossier School of Education. That same evening, he appeared on MSNBC’s All In With Chris Hayes to discuss the challenges of reopening schools. This would be one of many media appearances over the course of an anxious summer as the nation’s educators grappled with the transition to online learning and longstanding equity issues brought into sharp focus by the pandemic and civil unrest.

Long hours are nothing new to Noguera. In graduate school at UC Berkeley, he juggled his studies with a full-time job as executive assistant to the mayor of Berkeley while raising two small children. After he graduated in 1989, he managed a load that included serving as board president of the Berkeley Unified School District, high school teacher at a continuation school, and raising two more of his five children, all while becoming a new assistant professor at UC Berkeley’s School of Education.

He’s been prolific in his scholarship all the while, writing or editing 15 books and publishing over 250 articles and book chapters. He’s been on the faculty at UC Berkeley, Harvard, New York University and UCLA. “Before this whole concept of ‘public intellectual’ had its most recent rebirth,” a former colleague at UCLA, Professor Walter Allen, says, “he was functioning in that capacity.”

Noguera has emerged as a leader among a battalion of educators who have long been calling for a paradigm shift in how we educate. Now that the pandemic has turned life as we know it on its head and the movement for social and racial justice is demanding real change, the moment is ripe.

“We can’t return to normal,” Noguera told listeners during a webinar in June. “We have to return to something much better.”

By better, Noguera means more challenging and engaging, more responsive to student needs, and, fundamentally, more equitable. While some believe the answer to the inequities that plague schools is to throw money at the problem, Noguera notes that many well-resourced schools often don’t have great outcomes for students of color. While many schools certainly need resources, it’s not so simple.

For Noguera, just as important as examining where things go wrong is looking at success stories. Schools where “Black and Latino kids are succeeding” offer solutions, Noguera believes. He urges educators to “learn from what works,” and to closely examine “positive deviance”— low-income kids of color who succeed despite the odds they face. Noguera was once one of those kids, and he believes the key to helping more children succeed lies in creating schools where a holistic approach to education that addresses the cognitive, emotional, social and physical needs of students is at the forefront.

Why education?

Ron Dellums, the late congressman and former mayor of Oakland, encouraged Noguera early on to consider running for Congress. “Who knows if he was serious or not,” Noguera says humbly, but he did consider going into politics. In fact, Noguera was the student body president at UC Berkeley, where he helped organize the anti-apartheid movement, which led the university to divest more than $4 billion in South African investments. This experience taught him that broad movements for social change can lead to real changes in institutions and society. However, Noguera realized as he was serving on the board of Berkeley Unified and working as chief of staff to Mayor Loni Hancock in Berkeley that, “I didn’t like raising money or telling people what I thought they wanted to hear.” He wasn’t cut out for politics.

Noguera’s early years of scholarship were dedicated to studying adult education and political change in the Caribbean, a curiosity fueled in part by a desire to explore his Caribbean heritage. In the early ’80s, he read the work of the Brazilian educator/philosopher Paulo Freire, author of Pedagogy of the Oppressed. Noguera deeply admired Freire’s work, and it has had a strong influence on his thinking and scholarship throughout his career.

In 1982, shortly after he started his doctoral studies, Noguera, joined by Patricia Vattuone, who would become his first wife, left California for Grenada, the 133-square-mile tropical island in the Caribbean. There, the couple had their first son, Joaquin, and Noguera carried out his doctoral research. (Tragically, Vattuone passed away in 2006 from cancer.)

“At the time, I was primarily interested in the political changes that were occurring in the country,” Noguera says. “I wanted to know how ordinary people were being affected by it, and to what degree literacy was serving as an avenue for democratic participation.”

Drawing on Freire and his experiences in Grenada, Noguera came to believe that “education must be central to any movement for change, otherwise people can be manipulated by politicians who appeal to their fears.”

While he had earned his teaching credential at Brown University, in addition to his bachelor’s and master’s in sociology, Noguera initially did not envision pursuing a career in education. He went to UC Berkeley to study sociology and viewed teaching as a “way to get to learn about the Oakland community” and earn extra cash to support himself and his family while in graduate school.

But after two years in Berkeley’s mayor’s office, working on some of the most difficult and complex problems facing the city—crime, homelessness and economic development—Noguera felt frustrated. When he took the job, he thought he was “in a position to make things happen,” he wrote in his 2003 book, City Schools and the American Dream: Reclaiming the Promise of Public Education. Noguera always knew he wanted to be a force for good. (His Twitter bio lists “changing the world” among his interests.) But he soon realized that “perhaps I had been too naïve,” he wrote. “Why should I have thought that crime and poverty could be solved by one city, even as it plagued communities throughout the United States?”

Noguera was turned off by the grotesque amount of money involved in politics, and how changes pursued in a liberal city like Berkeley were often only symbolic. “The closer I got to the politicians,” he says, “the more cynical I got about politics. I truly believe that most politicians don’t lead; they follow public opinion, and, too often, work on behalf of the interest groups that fund them.”

Pedro recognizes that where there have been moments of progressive change, it’s been because individuals within those prescribed roles have pushed the envelope and the accepted boundaries.” — Walter Allen, UCLA Distinguished Professor of Education and Sociology

When a friend and principal paid Noguera a visit from East Campus, an alternative school in Berkeley that had “become a dumping ground for troubled kids,” Noguera’s political pursuits abruptly ended. The principal brought with him a bright, charismatic Black student and thought Noguera might be able to help persuade him to run for student body president. While some might have dismissed the teen based on his appearance and background, Noguera and the principal saw potential.

Noguera, so moved by the visit, left his job for a position at East Campus, where he was tasked with educating students who had been labeled as too challenging and disruptive for traditional public school. Noguera’s experience in the Berkeley mayor’s office had shown him how minimal the police’s impact had been in dealing with the crack cocaine epidemic of the 1980s, and he realized that a lot of his students were involved in the drug trade. Part of the issue, Noguera says, was about survival. They needed money, but there was more to it than that.

“While the police were focused on arresting the kids selling drugs on the street, I saw complicity at the highest levels,” Noguera says. “The Black community was feeling the burden of the crack cocaine epidemic, but lots of people from other communities were buying the drugs and profiting off the sales. Lots of people and businesses were involved, and that wasn’t seen.”

This experience was one reason why Noguera has focused much of his scholarship on the educational and social issues facing males of color, inspiring such work as his 2009 book, The Trouble With Black Boys … And Other Reflections on Race, Equity, and the Future of Public Education. “Sadly,” he writes in the introduction, “the pressures, stereotypes and patterns of failure that Black males experience often begin in schools.” Noguera wanted to change that by redefining the issue as an American challenge rather than a Black problem.

“My interest in education,” Noguera says, “has always focused on getting people to see how what’s happening outside of school impacts what happens inside of schools.” And his training as a sociologist has no doubt influenced his approach to education, Allen says, “and also his determination to achieve positive change within education, and to move the field, the practice and society towards social justice.”

Allen says that Noguera understands systems—especially bureaucratic ones. He has the ability to place schools within their historical context, Allen adds, and understands “the political factors that are operating that sometimes move people to positions that, personally, they don’t even embrace.”

This is not to say that Noguera believes educators are just cogs in the wheel. Quite the contrary, Allen says: “He has a great appreciation for individuals operating within those spaces. He doesn’t give you a pass of simply saying, well, you’ve been swept along by the machine.”

Instead, “he recognizes that where there have been moments of progressive change, it’s been because individuals within those prescribed roles have pushed the envelope and the accepted boundaries.”

Made in Brooklyn

Like many of us at USC Rossier, I first met Noguera over Zoom. He wore a T-shirt with “Made in Brooklyn” across the front and spoke from his garden, where he cultivates a bounty of kale, peppers, tomatoes and onions.

Casual, yet attentive. Serious, yet quick to laugh. A true “mensch,” says Marcelo Suárez-Orozco, chancellor of the University of Massachusetts Boston and former dean of UCLA’s Graduate School of Education & Information Studies, where Noguera was a Distinguished Professor of Education before joining USC Rossier.

Born in New York City in 1959, Noguera is the second of six children. His father, Felipe Noguera, the son of Venezuelan and Trinidadian immigrants, was a taxi driver and police officer. Millicent Noguera, his mother, is from Jamaica and stayed at home with the kids, a full-time job with no limit on overtime. “People often would ask my father, ‘How did you manage to send all six of your kids to college—and to such good ones?’” Noguera recalls. “And he’d say, he doesn’t know, ‘it must be their mother.’”

In Noguera’s early years, before they moved to Long Island, the family lived in Brownsville, a Brooklyn neighborhood Noguera describes as a place that “still hasn’t been gentrified.” Neither parent graduated from high school, but they deeply valued education. His father, once a member of the U.S. Merchant Marine, traveled extensively and loved reading; he believed that with a library card, you could get a free education.

He’s very collaborative, and he’s inspiring. There’s an excitement about the kind of energy [he brings]. He’s connected to the problems that we’re facing but maintaining some optimism. I think we all need that right now.” — Julie A. Marsh, USC Rossier Professor of Education Policy

The teenage Noguera was both an athlete and “accused of being a nerd” in school, experiences that exposed him to peers from all backgrounds. He made friends easily with a variety of students from his mostly White high school.

When it came time for his older brother to apply to college, an 11th-grade teacher who saw his potential encouraged him to aim high. That brother was accepted to Harvard. “I just assumed that I could go to a similar school and only applied to top schools myself,” Noguera says. He attended Brown University, where he studied American history and sociology, played rugby and attended apartheid protests alongside the likes of John F. Kennedy Jr., and found a mentor in the late Professor Martin Martel, a “chain-smoking” sociologist who took an interest in him during his sophomore year.

“Despite my working-class background,” Noguera writes in a recent essay reflecting on his time at Brown, “attending racially integrated schools had provided me with a valuable form of social capital that made it possible for me to advocate for myself and others, navigate rules and barriers to pursue my goals, and form strategic alliances with mentors, friends and associates based on recognition of our common interests.”

A dean for practice, policy and research

Even over Zoom, Noguera is a man you want to listen to. “He’s the light of the room,” says his daughter Naima Noguera, a photographer and camera loader living in New York City. Allen, who has seen him in many settings, echoes this sentiment, describing him as an “authentic guy” who can “connect with people across lines [and] statuses.”

A Google search of “Pedro Noguera” will return over 100,000 results. He is incredibly active in the public realm and, in an interview with Erin Gruwell, host of the Freedom Writers Podcast, Noguera describes this as a “blessing.” A former trustee for the State University of New York, Noguera also advises many public officials on K–12 educational policy, including Los Angeles Unified School District Superintendent Austin Beutner and New Mexico Gov. Michelle Lujan Grisham.

“It’s not good enough to sit and critique,” Noguera says. “We have to go beyond critique to provide real guidance on what should be done.”

"We have to go beyond critique to provide real guidance on what should be done.” —Pedro A. Noguera, USC Rossier Emery Stoops and Joyce King Stoops Dean

Though cynical about politics and impatient with the policy process, he’s not without policy suggestions. In a 2019 article published in The Nation, where Noguera is a member of the editorial board, he outlines seven suggestions to transform schools: funding special education; building capacity in failing schools rather than shutting them down; focusing on children’s physical and mental health; using standardized tests as a tool instead of a weapon; treating parents as partners rather than consumers; addressing the underlying issues that cause discipline problems; and shifting from top-down accountability to mutual accountability from a variety of stakeholders.

“He’s very collaborative and inspiring,” says USC Rossier Professor of Education Policy Julie A. Marsh, a member of the USC search committee that helped select the new dean. “There’s an excitement about the kind of energy [he brings]. He’s connected to the problems that we’re facing but maintaining some optimism. I think we all need that right now.”

When the search for a new dean began in 2019, “we wanted to make sure that we found someone who had leadership in the three key areas our school focuses on: practice, research and policy,” Marsh says.

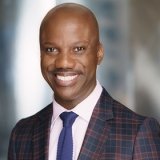

Shaun R. Harper, Provost Professor of Education and Business at USC Rossier and USC Marshall as well as director of the USC Race and Equity Center, has known Noguera for nearly 20 years. Throughout this span of time, Harper has found him to be “a warm person, serious scholar and courageous leader.” Noguera’s appointment, Harper says “is a significant win for our school and university. He embodies educational equity. We couldn’t have possibly found a better, more mission-aligned dean.”

Noguera’s years of public engagement made him an ideal fit for USC Rossier’s equity-focused mission, as did his extensive research on such topics as urban school reform, the conditions that promote student achievement, and race and ethnic relations. His decades in the classroom have given him both practical experience and influenced his research.

“A big problem in our schools is that we don’t teach kids the way they learn,” Noguera said at a keynote address at the Buck Institute for Education in 2019. “We expect them to learn the way we teach. And when they can’t do it, we say there’s something wrong with them or their parents.” Noguera’s teaching style embodies this student-centric approach.

Shelby Kretz, a UCLA PhD candidate and advisee of Noguera’s, notes the inquisitiveness and curiosity that Noguera cultivates in the classroom, which Kretz believes “fuels his research … because he truly is interested in understanding education from so many different perspectives.”

Earl Edwards, a doctoral advisee and teaching assistant of Noguera’s at UCLA, emphasizes how Noguera “actually focused on learning, rather than what was supposed to be taught.” Edwards also deeply appreciates Noguera’s openness for debate, and how he’s “willing to see you as an equal.”

“I’ve seen Pedro over the decades as a brilliant academic, a convener, a peacemaker,” Suárez-Orozco says. “I’ve also seen him as a truth-teller, and he always does it with no drama and with a big heart, which I think is very uncommon.”

What’s next?

Not just father to five, but also grandfather to four and uncle to a gaggle of nieces and nephews—family has always been central to Noguera. It’s easy to imagine, in pre-COVID times, the family’s back porch filled with loved ones, conversation and easy laughter.

Despite such a large extended family, plants outnumber the people at his home at a staggering ratio. In every nook and cranny, there is greenery.

One plant Noguera adores is the banana tree in his front yard. A school near his Culver City home gave the tree to him when it was just a sapling, barely a foot tall. In the four years since, under Noguera’s care, it has grown to more than 15 feet and borne fruit on two occasions. A fitting metaphor.

Starting a new position is never easy. Starting a new position during a viral pandemic and months of social unrest is even harder. While Noguera has met many in the USC community via Zoom, “it’s not the same as interacting directly,” he says. “I’m a people person, and I feed off of interaction.”

Noguera and his wife, Allyson Pimentel, a psychologist, meditation teacher and incoming associate director of Mindful USC, have an 8-year-old daughter, Ava, whose adjustment to online school hasn’t been easy. Like many parents, Noguera and Pimentel juggled their own work with that of home-school teacher in the spring and saw Ava struggle. She is now in a learning pod.

One blessing, Noguera notes, is that former Dean Karen Symms Gallagher left USC Rossier “in great shape.” The next challenge, he believes, “is to take [the school] to an even higher level of impact on the field of education.”

He sees the role of a dean as a “kind of a facilitator. … I want to work with faculty, students and staff to make the school influential in the field.”

One of his first initiatives is a webinar series that will bring USC Rossier scholars together with other top education thinkers to consider the transformation of schools from a variety of angles. “I want Rossier, as a whole, to be in the mix of figuring out how to address the complex challenges facing schools,” Noguera says.

In addition to the webinar series, in his first year, Noguera plans to provide funding for a research initiative to uncover how racial injustice is perpetuated through education, launch a civic education initiative with a focus on fostering constructive debate skills, and begin an examination of USC Rossier’s degree programs to see if they are truly advancing equity. Reveta Franklin Bowers, chair of the USC Rossier Board of Councilors says that, "Given the challenges COVID-19 has imposed on our schools, faculty and students, combined with the disproportionate impact financially, racially, emotionally, it is critical for Rossier to be led by someone with Dr. Noguera’s experience, skill set, conviction and voice.”

He will have lots of help, from faculty, staff and students, as well as USC leadership. “Dean Noguera will draw on his deep expertise as he assumes responsibility for upholding and advancing USC Rossier's mission to strengthen urban education through cutting-edge research and real-world experience,” USC President Carol L. Folt says. “I know he will build on the school's strong foundation to chart new paths in education and tackle the profound challenges that must be overcome if we are to advance our society. We are eager to support him as he hits the ground running.”

More than anything, Noguera believes in the power of educators.

“When the door closes, the teacher has a lot of power,” Noguera says, “but they don’t realize how much. We have to remind teachers that they do have power. And they have to use it for good.”