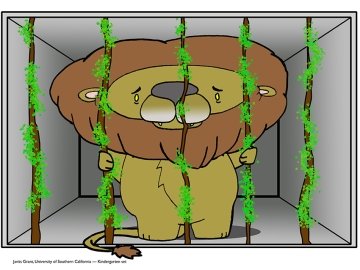

A Latina kindergartner from the Ontario-Montclair Unified School District sits in the back of her classroom, responding one-on-one to questions designed to probe her problem-solving ability and gauge her curiosity. After looking at a drawing of a lion in a cage made out of plants, she is asked, “How can it get out?” Many of her classmates said the zookeeper should be called, while a few others suggested the lion eat the plants. Instead, she asks: “Why does he want to get out? Where would he go? It would be dangerous for him.”

While there is no correct answer, less typical responses like this kindergartner’s may serve as indicators of potential giftedness.

This session and others like it are part of Project CHANGE, a study led by USC Rossier Professor of Clinical Education Sandra Kaplan and funded by a $1.7 million grant from the Jacob K. Javits Gifted and Talented Students Education Program of the U.S. Department of Education. A second Javits grant, Reach EACH, is supporting research to improve reading achievement of all students in a heterogeneous classroom, including special needs students, using a curriculum designed for gifted students. The research builds on more than three decades of work by Kaplan in gifted and talented education (GATE).

This question was from a set of curricular task cards that has been developed and researched to provide a nontraditional means of identifying giftedness in students of academic, cultural and linguistic abilities who have largely been overlooked by traditional methods of identification. The study also focuses on earlier identification, while serving as a catalyst to stimulate critical and creative thinking skills among all students.

Diverse schools of thought

GATE programs traditionally have primarily employed only intelligence quotient and achievement test scores to identify ability. While that approach maintains numerous proponents nationwide, Kaplan’s investigations show that the reliance on those two criteria leads to underrepresentation of students from low-income families with cultural differences and who possess limited English-language skills, are in foster care or have disabilities.

Many view the gifted, English-learner and special education populations as distinct groups. The reality is that an individual student could be all three of those.

“In California, we see a disparity in terms of identification,” Kaplan says. “While there is evidence that the potential for academic giftedness exists across all groups, many urban school districts do not manage to discover gifted and talented students from underrepresented populations with the same frequency as they do students from other societal groups. The pool of gifted students should reflect the diversity within a school.

In reality, it doesn’t match, and, as long as we keep emphasizing standardized test scores, it probably won’t match.”

Through the Project CHANGE grant, Kaplan and colleague Jessica Manzone PhD ’13 aim to identify more underrepresented children as gifted by emphasizing behavioral indices rather than test scores, while also helping teachers see their students in a different way.

They hope to build on a national effort to encourage teachers to become identifiers and instructors of talent, abilities and potential in young learners, rather than solely perceiving themselves as nominators of giftedness.

To facilitate the goals of early identification, teachers are using a curriculum that gives students opportunities to demonstrate talents, abilities and giftedness that might be lying dormant in other types of curriculum.

“We’re looking at economic, cultural, linguistic and academic diversity,” Kaplan explains. “But what makes us unique is that we are looking at children who are pre-K to second grade.” Children generally are not tested for giftedness until second grade or later.

The longstanding reasons for delaying such testing include a belief by some that, developmentally, giftedness doesn’t mature until age 7 or 8 — or that certain schooling is required before a student can show a particular aptitude, such as being able to write in order to demonstrate linguistic ability. Much research refutes this idea.

An inclusive pedagogy

Kaplan’s approach can be administered in regular classrooms in a setting comfortable for students. While she employs nontraditional instruments to identify giftedness, her lessons center on four traditional GATE teaching standards: depth, complexity, acceleration and novelty. She emphasizes open-ended questions, interpretive play and other prompts that challenge children to share the rationale behind their thinking and abilities.

Curricular lessons teach students, for instance, to use “because” as a lead-in to their evidence, as in “I think this because….” Or if a class is reading Cinderella, children are not asked close-ended questions such as “Who is the main character?” Or, “What is the setting?”

Instead, they discuss what “happily ever after” means, or how the story would change if the glass slipper were a regular shoe.

This method allows all children an equal opportunity to participate in the giftedness identification process, as they no longer have to wait to be nominated by a teacher in the second or third grade. It also enhances critical and creative thinking among all students.

“Every student has the right to be appropriately challenged and to engage in the development and activation of potential,” Manzone says. “Whether or not it ever leads a student to a formal gifted identification or not, doesn’t make any difference. We’ve raised the level of academic rigor for all children.”

Infusing these types of lessons into the regular curriculum at an earlier age has another distinct advantage — providing a strong framework for future learning.

“We want to help students develop an insatiable appetite for learning — and help them learn how to learn,” Kaplan says. “We are interested in developing intellectualism as well as intelligence.”

“If we can catch students at the preschool level and get them thinking in divergent ways, then that is going to imprint how they become a scholar and a thinker as they move through the grade levels,” Manzone adds. It also helps prevent children from becoming disengaged with school.

Karen Anderson, who oversees the GATE program for the Pasadena Unified School District, agrees. “Dr. Kaplan’s research with younger children is really significant in moving our perceptions of the labeling of gifted children,” she says. “Sometimes it’s too late by the time they get to third grade. They have perceptions about learning that are already embedded that are not helpful to their development of critical and creative thinking. Or what they’ve learned is actually hurtful and inhibits the development of such thinking.”

For more than a decade, Anderson has served as a demonstration teacher with the California Association for the Gifted, as well as for Kaplan’s USC Summer Gifted Institute — now in its 33rd year. She also is an adjunct professor in USC Rossier’s Master of Arts in Teaching program.

Helping teachers incorporate the pedagogy into their own classrooms counters unintentional academic prejudice, Manzone notes.

“One of the best things to come out of the grant lessons is hearing teachers say, ‘Wow, Johnny really did an excellent job in that lesson. I never thought he could do X or Y.’” It’s the teacher’s perception that changed — not the child’s ability.

“It’s not about gifted students being separate,” Anderson adds. “It’s about inclusivity. That’s what I value most about this work.”