Exemplary teaching is often described as an art, but is there science behind it, too?

A research team led by a USC Rossier professor is aiming to provide some answers.

Mary Helen Immordino-Yang, whose research at the USC Brain and Creativity Institute blends psychology, neuroscience and education, is known internationally for her research on the critical role that emotion plays in learning. Now she is extending her inquiry to teaching, with a study on how highly effective teachers think about their students and what brain dynamics are activated when they are reflecting on their students’ work.

“We’re trying to understand the kinds of practices and thought patterns effective teachers engage in that promote intellectual and personal development in their students,” Immordino-Yang explains. She hopes the study will shed light on the “deep cognitive, emotional and social work” that she believes undergirds the most potent secondary teaching, “that goes far beyond simply understanding your content and being able to manage your classroom effectively.”

To that end, she is leading a research team that is tracking 40 teachers from Artesia High School in the ABC Unified School District and Intellectual Virtues Academy, a Long Beach public charter school serving middle and high school students.

The two-year study, funded with a $300,000 grant from the John Templeton Foundation, involves classroom observation and collecting physiological and psychological data from the teachers. Over the summer, the first set of 15 teachers participated in interviews and underwent brain scans at the USC Brain and Creativity Institute, where Immordino-Yang is a faculty member.

“Great teaching is not just about the things you do, the words you say,” says Xiaofei Yang, a senior research associate in Immordino-Yang’s lab, who, along with USC Rossier educational psychology doctoral student Christina Krone, is helping to conduct the study.

“We think great teachers have a mindset that distinguishes them,” Yang, who is not related to Immordino-Yang, continues. “It might be something they can articulate. But it might also involve implicit processes that they might not be aware of. If we can better understand these, then perhaps we can target them in teacher education programs and professional development.”

The study is focusing on secondary teachers because Immordino-Yang sees a pressing need to design developmentally appropriate schooling for adolescents.

“Most research on how teaching practices impact development and learning focuses on younger children,” she says. “However, it is now clear that adolescence is a second period of intensive brain development, and that targeted interventions and educational opportunities at this age can give youths a second chance to rework the brain networks that undergird thinking. This can make a huge difference to adolescents’ transition into higher education and to their well-being as adults.”

What qualities define the best secondary teachers has long been a matter of debate. Subject-matter mastery and the ability to command a classroom are considered essential by most experts, along with knowledge of fields such as child development and learning theory. Many other researchers put personality and character front and center. Immordino-Yang, who believes that young people’s social-emotional and scholarly capacities are “co-dependent,” is unique in her use of interdisciplinary interview, classroom observation and neuroscience studies to better understand great teaching.

We’re trying to understand the kinds of practices and thought patterns effective teachers engage in that promote intellectual and personal development in their students.”

—Mary Helen Immordino-Yang

A former seventh-grade teacher, she came to USC in 2006 as a postdoctoral fellow at the Brain and Creativity Institute and quickly began making inroads with research on the neurobiology of “social emotion” and its impact on adolescent learning. Emotions such as compassion and admiration, she wrote in her 2015 book, Emotions, Learning, and the Brain: Exploring the Educational Implications of Affective Neuroscience, “form a critical piece of how, what, when and why people think, remember and learn.” Or, as the title of her widely cited 2007 paper, co-written with BCI director and Dornsife Professor of Neuroscience Antonio Damasio, put it, “We Feel, Therefore We Learn.”

“Mary Helen is a pioneer in the field of education, having combined traditional studies in education with neuroscience,” says Damasio. “Her approach to the study of teachers reflects the novelty of her perspectives.”

The research on teachers grew out of a project to evaluate the effectiveness of the curriculum at Intellectual Virtues Academy, which is dedicated to building students’ intellectual character, including traits such as curiosity, wonder, open-mindedness and creativity. A core tenet of the school is that intellectual growth is most likely to occur in the context of trusting relationships with teachers who model those habits of mind.

“When you take seriously the concept of teaching for character, you are taking seriously the agency and importance of the student,” says James McGrath, principal of Intellectual Virtues Academy High School. “The best way for the student to feel that is to have genuine, caring relationships with teachers.”

Intellectual Virtues Academy’s 100 high school students are predominantly Latino and Black. Most students come from low-income backgrounds, and about 50 percent enter the school reading far below their grade level. Despite these challenges, the school has scored above the national average on standardized tests of math, reading and critical thinking for three consecutive years, McGrath says.

These results suggest the effectiveness of a model that considers the student-teacher relationship as crucial as a rigorous curriculum and high standards. And it made Intellectual Virtues’ middle and high school teachers attractive candidates for the study.

“There is something really important about the social component of teaching, fostering relationships with students and communicating that you believe that they can be successful,” says Krone, a former high school science teacher, who is overseeing the fieldwork.

In later phases of the study, the researchers hope to build “dynamic systems models of the ways in which students and teachers are engaging with one another,” Immordino-Yang says, “and establishing a culture of learning that sets the stage for deep engagement with ideas and ultimately for brain development.”

The 40 participants in the current study are all classroom veterans who were identified as excellent teachers by school leaders. One of them is Amelia Bagheri, who teaches chemistry and physics at Artesia High, a 2013 California Distinguished School in Lakewood with a predominantly Latino enrollment.

“My secret,” she says, “is convincing kids at the beginning of the year that they know me. I tell about my favorite things. I get them to tell me their favorite things. I try to learn their names super fast. And I try to give a lot of positive attention because I want them to trust me.”

Jonathan Le Shana, who teaches social studies at Artesia High, agrees that the classroom environment created by the teacher is crucial.

“Most of my energy on a daily basis goes into providing that good environment,” he says. “That means that students feel comfortable, loved, cared about in the classroom. That’s important for any human anywhere, but it’s especially important for students from difficult backgrounds—low-income or with experiences of violence—of which we have many.”

Like Bagheri, he was eager to join the study, despite the pressure of having five researchers watching his every move during a civics class last spring. They fitted him with a microphone and trained a camera on him. Because they also are investigating how challenging situations may inhibit good teaching, they strapped a device on his wrist to capture stress responses. He had one piece of equipment of his own: a lightsaber he used as a pointer during an outer space-themed trivia game designed to help his students review for an exam.

When his principal invited teachers to participate in the study, Le Shana immediately sent him an enthusiastic text. “I said I’d love to do this. I love that they are focusing on the neurological responses of teachers. And I’d never had my brain scanned and thought it would be a neat opportunity to do that.”

After completing the classroom observation, the researchers invite teachers to the lab, where their responses to various stimuli are recorded. In one activity the participants view videos of other teachers demonstrating teaching strategies, such as how to encourage class participation, and are asked to evaluate whether the methods shown are having an impact on learning and why.

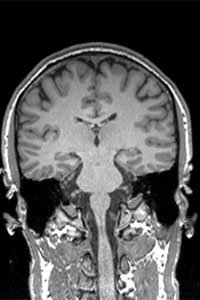

In another exercise they are asked to grade their students’ papers and reflect on each pupil’s work while undergoing brain scans in the MRI machine. The researchers theorize that distinctive patterns of neural activity will appear when effective teachers are thinking deeply about how to support their students’ development.

“We want to see if there are differences in brain dynamics when they are engaging with their students’ work,” Yang says. “We think that for great teachers the task [of grading] is not just about the work in front of you, whether it’s right or wrong, but about the history of the student, how they performed the entire semester and what to do to help that student in the future. Our idea is that great teachers engage with the broader personhood of a student more than other teachers do, and tailor their feedback accordingly.”

Paul Burns, who teaches science to seventh- and eighth-graders at Intellectual Virtues Academy Middle School, agrees that engaging with students is essential.

“For so many years I was told: ‘You’re weird. Why do you spend so much time connecting with the kids? You should just tell them what’s right and what’s wrong,’” he says. “But I feel so much for them; it makes me weepy sometimes, connecting with them. If a student is struggling, I will stop the whole class and say, ‘Let’s struggle together and get it.’ It’s about growth and love. And I think they feel it.

“So, to have a scientist come in and say, ‘Let’s see exactly what it takes for a person’s brain and body to be a great teacher,’” Burns adds, “feels so validating.”

Ultimately, the researchers want to use their findings about the social, emotional and cognitive work of great teaching to improve secondary education. Immordino Yang is working with Linda Darling-Hammond, president of the California State Board of Education, to translate the new science into policy aimed at wide-scale change.

“Everybody understands that preschool teachers need to be able to engage with the kids socially and emotionally,” Immordino-Yang says, “because if you didn’t it would be a disaster, right?

“But we expect high school kids to compensate somehow when their teachers are not engaged with them, even though the high school years are another period of profound social, emotional and brain development. We neglect that opportunity in the way we design high schools and train high school teachers.

“We’d like to understand the range of ways really effective teachers engage with young people so that we can learn from one another and so we can start to build a science of secondary teaching as a profession.”