“I mean, we thought this thing with heartbeat would tell us something about acculturation—but the fact that it actually works is vastly surprising to me. I mean, my jaw’s still on the floor.”

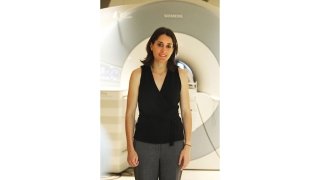

It is January 2015, and USC Rossier Associate Professor Mary Helen Immordino-Yang is two years into a five-year longitudinal study on adolescent brain and social development. While there is still much ahead to uncover and explore, the start of the year also marks the completion of the first wave of the study, and the neuroscientist clearly relishes the opportunity to discuss the potential implications of her team’s discoveries.

The source of such surprise and enthusiasm is a heart-rate test, one of the elements of the larger study supported by the National Science Foundation. The project is designed to “examine how youths from two ethnic groups with different norms around emotional behavior, Latino American and East-Asian American urban adolescents, come to feel complex social emotions in culturally appropriate, individually variable ways.”

In contrast to some notions about thought and reason, Immordino-Yang has long believed that emotional connection is at the root of deep learning, and thus effective education. “Traditional educational approaches think about emotion the way Descartes did; emotion is interfering with your ability to do well in school, to think rationally. Neuroscience is showing us that that is absolutely not the case—when you take emotion out of thought you have no basis for thought anymore. So we’re trying to understand how socially constructed emotion shapes learning, academic development and identity.”

The benchmarks for this project were actually set in an earlier study, one Immordino-Yang conducted with three groups of participants: USC students of American descent (monolingual English speakers); English-speaking second-generation East-Asian American USC students; and Chinese students at Beijing Normal University.

When comparing the three groups of participants, says Immordino-Yang, her team found “these very systematic cultural differences in how neural activity corresponds to emotional experience. If the effect is related to cultural exposure, then we should see that the Asian American kids show a hybrid pattern because they’re bi-cultural, navigating between American and Chinese identities. Sure enough, we get this statistically significant intermediate effect, where the Asian Americans are in the middle, which shows you that this is an effect of the cultural world. And so what we’re exploring in the adolescent study is how those differences get there—how adolescents’ exposure to family relationships, cultural values, community violence and other factors shape the neural processing of emotional experience both in and out of school.”

The current NSF study is an unprecedented attempt to investigate the root causes of that intermediate effect and its implications for learning. As Immordino-Yang notes, there are no other longitudinal studies of social brain development in adolescents. Over the past two years, starting in 2013, her group has examined and interviewed 65 adolescents. Each participant came in for a full day of testing designed to measure various psychological tendencies and responses.

“She uses a case study approach, but a case study with 60-something kids,” remarks Rebecca Gotlieb, one of Immordino-Yang’s doctoral students, “so we really get to see in depth a number of factors.”

The process involves introducing the participant to 40 true stories about remarkable adolescents from around the world. These documentary-style narratives have been categorized into four conditions based on their intended affective impact on the viewer. There are stories intended to elicit admiration for virtue (like the one about Nobel laureate Malala Yousafzai, for instance); compassion for physical pain; admiration for physical skill; and compassion for social pain.

"We’re trying to understand how socially constructed emotion shapes learning, academic development and identity.”

Once the participants have explained their reactions in a private interview, they enter the MRI scanner, where they are shown a five-second clip from each video and asked to rate how the story makes them feel at the present moment. Next, they are matched with an interviewer who shares their ethnic background, who interviews the participant about their identity, personal and family life, in addition to other factors. This is meant to gauge their personal values and perception of their relationships.

Then comes the aforementioned heart-rate test.

“We ask them to run up and down the stairs in the psychology department until they can clearly feel their heartbeat. Then we hook them up to the ECG and show them their heartbeats; then we turn the computer around and ask them to continue counting and marking their heartbeats for us.”

As Immordino-Yang notes, ideals around how to express emotion are different in the two cultures represented in the study. “In one cultural group, the East Asians, the ideal is sort of Confucian—calm your body so you can focus outwardly into the social world,” she remarks. “In the other cultural group, the Latinos, the ideal is to be more embodied, to ‘trust your gut’ and pay attention to your heart because your own body is giving you intuitive information about the social world.”

Interestingly enough, the ability to feel visceral sensations seems to predict what culture —parental/home or American/school—the subject more identifies with.

“What we find is that among the East-Asian American kids, it’s the kids who are not particularly sensitive to their heartbeats who are saying they strongly hold Asian values, whereas among the Latino kids, it’s those who have a better ability to feel their heartbeat who are saying they strongly hold Latino cultural values,” says Immordino-Yang. “What that tells us is that kids’ natural awareness of visceral sensations may predispose them toward constructing a particular identity. It’s showing us how a very basic biological tendency, which we know is anatomically based, which is mainly kind of innate, is predisposing kids to adopting a particular kind of psychological self, with implications for how they act, what they believe in and who they strive to become.”

Such findings, she suggests, could have important implications for education and policy. Once more is understood about how the social world and natural biological tendencies interact to influence adolescents’ development, the obvious next step is to think about more informed designs for the part of the social world adolescents spend a great deal of time in—the education system. “How do we orchestrate an education system that optimally supports youths in developing the kinds of selves that we are discovering lead to resilience, to creativity and to complex cognitive abilities to think critically and ethically about academic and world problems?”

Education, she believes, should be more self-directed than it currently is, recognizing the fact that cultural influences may shape youths’ approaches to achieving particular goals. In other words, we need to implement high standards for achievement, while at the same time supporting diverse paths to that achievement and student ownership of those paths.

“We need to move toward systems that have very high standards for the complexity of thought and the kind of qualities of thought that we expect of our students and of our teachers, without standardizing as much the means to the end,” she remarks. “I think that a lot of times our goals are very poorly defined. To just be able to solve algebra problems is not a meaningful goal. I think the Common Core and other initiatives that are gaining more ground in education now are actually moving in this direction, trying to help people understand the kind of thinking educational experiences aim to support—as opposed to merely delineating the factual knowledge kids should be able to regurgitate.’”

Now that the study has reached the halfway mark, and the team is beginning to bring back the adolescents they last saw two years ago, what lies ahead for Wave 2, and the rest of the study?

“We’re starting to look at how kids’ executive function ability is related to their ability to imagine, to think about the future and then to make that future happen,” says Immordino-Yang. “So we’re finding some very intriguing trends in which kids’ ability to imagine within the social-emotional space is potentially more important for success than is their standardized intelligence. There have been some findings in those data that are very surprising, and actually super cool.”