In many ways, one could say that teaching found Brenden Scott MAT ’22. The Bay Area native, who was raised by his single mother in Los Angeles, excelled in the sciences and athletics in his youth. Armed with a track and field scholarship and plans to attend medical school, Scott enrolled at California State University Northridge in 2015. But when he faced struggles in the final year of his undergraduate studies, a fateful meeting with one of his professors would find him putting his medical aspirations on hold in order to answer a call to teach. Scott embarked on this path not only to pay forward the support from educators who shaped his life, but also to have an immediate impact on the Black and Brown children of Los Angeles.

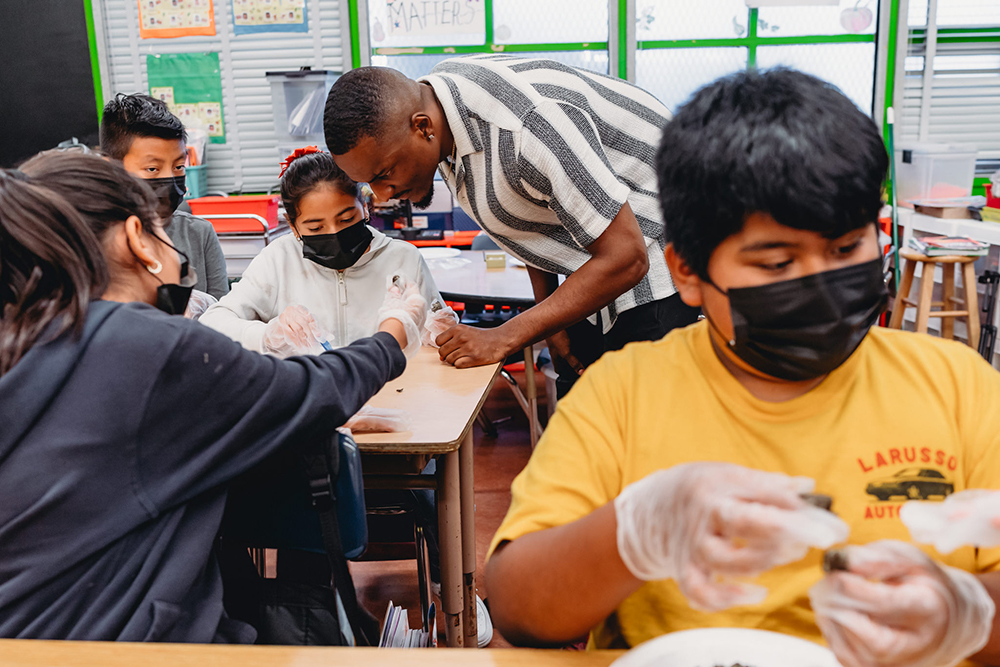

Scott, who was a student commencement speaker, graduated on Friday, May 13, 2022 from USC Rossier’s Master of Arts of Teaching program. Through the program, he found support from faculty and a mentor in Mrs. Hamilton, his guiding teacher at 93rd Street Elementary where he has student taught fourth grade since the fall of 2021. Along the way, Scott also discovered his talent for teaching. This August, Scott will continue to teach the fourth grade at KIPP (Knowledge is Power Program) Compton Community School.

Scott spoke with USC Rossier about the challenges of being a student-athlete, his year in the classroom and the importance of representation in education.

You were born in the Bay Area, but moved to Los Angeles as a kid. When did you move to L.A., and was there anything you missed about the Bay Area after moving to Southern California?

I moved to LA when I was in upper elementary, in fourth grade. My parents separated, so my mom and my siblings decided on a fresh start in Southern California. We’ve been here ever since. I lived in Carson up until I graduated from undergrad in 2020; now I’m in Long Beach.

One thing I will say about the Bay area is that it is slower-paced. I didn’t realize that until I grew up and witnessed how fast trends change here in Los Angeles and how much of a rush everybody is in. When I got to college, however, I found it interesting that the majority of my closest friends actually came from the Bay. I didn't miss much it except for my family. Only my immediate family moved out here. I have all my cousins, aunts, uncles and grandparents still up north. We really only get the time to see them during holidays.

Looking back, are there any childhood memories that you feel shaped the path that you’re on now as an educator?

I had one teacher in particular, Ms. Cox, at Leapwood Avenue Elementary in Carson. And she was tough—but it was tough love. Tough love isn't something that I appreciated until later, but she was a phenomenal teacher. She was my fourth-grade teacher, and then she moved up with us to fifth grade. She was my first African American teacher. Just seeing myself represented and her identifying with the same culture was so special. She was able to teach us in a way that really stuck with me. I was considered academically advanced, so by the time I enrolled in middle school I was in the School for Advanced Studies at Carnegie Middle School in Carson. I don’t think I would have gotten there without her help. But the moment I left her classroom, my academics began to decline. I was no longer confident in my abilities. I wasn't represented, and I was the only one in the classroom that looked like me. Naturally, I felt as if I didn't belong. That’s when I realized the significance and importance for there to be African American educators in the classroom.

You were a track and field athlete at California State University Northridge. How did you discover track and field as a young athlete, and what events did you compete in?

I started running track when I was four. My dad was my coach, and I got really, really good at it. I broke national records. I won national titles and championships. But I started so young, that by the time I got to Carson High School, I wanted to give it up. It stopped being fun for me. I wasn’t in love with the sport anymore, but I knew I was talented enough to get a free education, so I persevered. By my senior year of high school, I had matured and was focused and fortunate enough to get a track and field scholarship to Cal State Northridge. I was recruited for the triple jump, and I ran a decent split on my high school's four-by-four team. When I got to college, I focused on the 400.

What are some of the unique challenges facing student-athletes? Both in high school and in college?

Being a student-athlete, you don’t have time to do anything but be a student-athlete. And it’s more like an athlete-student; you’re an athlete first. Unfortunately, that’s how it works. I didn’t get to explore my own interests until after I graduated, and I’m still currently doing that now.

I had an amazing youth track and field career. When I finally got to high school, I was dealing with anger from my father no longer being around. That, and the stresses of chasing a scholarship, took the fun out of it. I lost sight of what I was really doing it for. In college, time management was the biggest struggle for me. In classes where I should have gotten an A, I did the bare minimum because I literally just did not have the time. We traveled from Thursday night till Sunday, so I was only on campus Monday to Wednesday. However, I did learn how to stay disciplined. I had to sacrifice my social life, my love life. It was all about time management, and when I finally figured that out, I began to flourish. I always tell myself, if I can get through being a student-athlete, I can get through anything because that was the toughest time of my life.

There are times when I felt exhausted. To deal with the stress I wrote poems. I found myself going to different open mics, and that helped me through a lot. It took me away from the traffic, away from school and it grounded everything.

You helped tutor fellow student-athletes in upper-level mathematics, biology and chemistry, and you majored in pre-med. What you drew you to the STEM field in particular?

I was always interested in being a doctor. I knew it would be a prestigious career, and I wanted people to be proud of me. In high school, I was in the Academy of Medical Arts at Carson High School, so everything was geared toward medicine. I fell in love with the idea of being in a field that helps a community. I was excited to learn about the body. Everything was fascinating to me, and it was challenging, which intrigued me. I didn’t want to be in a career that I would be bored with, and with medicine, there is always something new.

At what point did you know you wanted to be a teacher?

In college, I wanted to go pro in track and field, but my body was done. I started getting hurt, and so, I had to change course. I asked myself, “What am I passionate about?”

So, it wasn’t until I started to struggle athletically that I discovered other passions such as teaching. I lost my track and field scholarship and was looking for ways to get through undergrad. I was dead broke. I turned to the Africana Studies Department at Northridge, and I went to one of my professor’s office hours one day, just to visit and have a venting session. That day Dr. Gammage offered me a research job, she told me about a scholarship I could apply to and invited me on a service trip to Africa.

After that, I felt I needed to give that same support to students that don’t have it. I was pre-med for four years, but I realized I have to teach. It was calling me, but I was running away from it, honestly because of the low pay. After my conversation with Professor Gammage I felt, more than ever, the need to be a teacher. It had been in the back of my head, but that confirmed it. I was like, “God, OK, I hear you. I will do it.”

Is there anything in particular that drew you to elementary education?

Funny story. When I applied to USC, I thought the multiple subject teaching credential meant I could teach any subject I wanted. I didn’t know that it limited me to elementary. My goal originally was to be a science teacher, because that aligns with my medical school ambitions. When I first wanted to go to medical school, it was to be a pediatrician, because I love kids. So, me being put in the multiple subjects’ program, was almost perfect.

What’s been one of the biggest challenges you’ve faced in the MAT program?

I had to take a semester off for personal reasons, but I’ve always had the support of my professors. Every semester, I’ve had a professor, at least one, who went above and beyond, making sure I was taken care of. I wasn’t sure what the community would look like here, because it is such a big school, but they really care about their students.

I had Professors Akilah Lyons-Moore and Eugena Mora-Flores my first semester. When I was going through a lot mentally, I made some poor life decisions, but these professors were so great to me. They kept checking in on me and made sure I had the resources I needed to thrive.

The semester I came back, I met Professor Margo Pensavalle. She’s retiring soon, and I feel sorry for the students coming in because they’re going to miss out on a really great professor. She’s been very, very supportive and understanding. She just gets it.

Every semester, I’ve had a professor, at least one, who went above and beyond, making sure I was taken care of. I wasn’t sure what the community would look like here, because it is such a big school, but they really care about their students.—Brenden Scott MAT ’22

What has your student-teaching experience been like?

It’s been really joyful. My guiding teacher, Mrs. Hamilton, is another fellow African American—I don't know how it keeps working out this way. She’s allowed for me to get comfortable. I told her I was pre-med first, so it took me a while to warm up to teaching and being around kids. I'm very shy at first.

The first semester I didn’t warm up until November. She was very patient with me, and she allowed me to make mistakes. But the hardest part so far, hasn’t been teaching. The hardest part has been dealing with the whole child and dealing with their lives outside of the classroom. The stories that you hear from them: not being financially stable, we had a kid whose dad committed suicide and a kid whose dad died of COVID. I want to help so much, and I can’t. There’s only so much that I can do, especially on a teacher’s salary. It’s so hard to hear these stories and not be able to do anything.

Has there been anything that surprised you about teaching?

One thing that really surprised me has been student behavior. They understand that I am a student teacher—I’m not perfect. They allow me to make mistakes, and they’re really helpful, especially when I’m recording. They know, “Okay, we’re going to sit up straight; we’re going to really help Mr. Scott out.” They’re also so grown. Times are changing—they’re into Tik Tok, and nails and hair. I’m very open with them and them with me. We really laugh all day—that makes my job so much easier.

What do you think schools could be doing better right now?

I came into the classroom just a couple of months post-COVID. I feel like this year alone should have been about getting the child acclimated to physically being at school and maturing the child. The last time they were at school, they were in the second grade. Now, they’re in the fourth grade. I’ve seen them grow so much, and I think I’ve had a lot to do with it. My students think I’m just the coolest. They like hanging around with me at recess and lunch. I can see my personality in them now.

Schools are so focused on testing. There’s a test about twice a month. You do not need to assess a child that much. It sucks to see them stressed out over tests and their grades falling. Schools need to let a child be a child and make mistakes. We’ll see their growth at the end of the year; we don’t need to see their progress every other week.

What has been your greatest challenge while teaching?

I taught a lesson on poetry. I performed a piece, then we did a writer’s workshop and a poetry slam. One of my students wrote a poem, and in the poem, he wrote, “No, no, don’t touch me there, is what I’ve told my uncle, but he doesn’t seem to care.” That was the hardest thing for me to deal with, because I instantly wanted to fight and protect my student. As a mandated reporter, I had to report it, but as a person, I wanted to talk and see what’s going on. I know how uncomfortable that can be. It’s more than teaching. I don’t know if people understand that. That’s the most challenging part—is that it is more than teaching.

You grew up in a single-parent household, and you’ve said one of your goals as an educator is to empower Black youth and assist single-parent households. What are some of your ideas for how to go about doing this?

Since I was in high school, I’ve wanted to start a nonprofit to help single mothers. I’ve been through that struggle. It is a miracle that I made it out alive. It’s not pretty, the financial struggle, having to navigate—especially if you go to college—by yourself. So, I’d like to create a program that allows these families to have the same opportunities as others, whether that’s providing their kids with a male mentor, providing financial support, meals or scholarships. I would start by asking families, “How can I support you?”

You were selected to speak at commencement. What one piece of advice do you have for current and future MAT students?

Be true to yourself, in all that you do, in every assignment, in your teaching practices and your student teaching. Don’t be afraid to be you and put your personality on things. There were assignments where I wasn’t sure I was completing correct, but I was like, “This is me.” And I was proud of it.

But the hardest part so far, hasn’t been teaching. The hardest part has been dealing with the whole child and dealing with their lives outside of the classroom. —Brenden Scott MAT ’22

What’s next for you?

What is next for Mr. Scott? I have to get used to that name. I enjoy teaching, and I’m going to teach for a few years before I head to medical school. I’m taking two classes over the summer, that will fulfill my entry requirements for medical school.

I was hired by KIPP (Knowledge is Power Program) schools at their location in Compton, which was perfect because that community is 60 percent African American and 30 percent Latino. I have heard a lot of negative things about charter schools, but once I got there, and met the staff and students, I thought, “Wow, I can see myself here.” I’ll be teaching fourth grade there in the fall.