Gale Sinatra’s Aha-moment came in Salt Lake City in the mid 1990s. A young researcher at the University of Utah, she was studying the relationship between reading and learning. In a reading study with adults, she had chosen what seemed to be an interesting but innocuous scientific passage on human evolution.

She was dumbfounded when her participants reacted with raw emotion.

“They said things like: ‘I can’t tell my family any of the information I just read. They would disown me,’” recalls Sinatra, now a professor of education and psychology at USC Rossier. In the fall she will be installed as the Stephen H. Crocker Professor of Education.

The passage was on evolution, and many of her study participants, it turned out, believed their faith to be in conflict with the science.

Comprehension wasn’t an issue. They clearly had understood the reading. But they categorically rejected it.

A common response Sinatra heard in her assessment interviews: “If I were to believe that I was related to an animal, I would have no reason to go on living.”

“That just floored me,” she recalls. “I had never before encountered such personal angst and internal struggle over a perceived conflict between one’s worldview and science.”

That research study changed the course of her professional life, and has led to the present moment. Sinatra is now a thought leader in the field of educational psychology, specializing in untangling the complex web of emotions and motivations that lead to successful learning — or to science resistance.

In August, she will be installed as president of the American Psychological Association’s educational psychology organization, Division 15. It’s a high honor and major responsibility, as each APA division is independent and shapes its own agenda. Appropriately enough — given her expertise in the public understanding of science — Sinatra plans to focus her presidency on the theme of sustainability, both environmental and organizational.

“I had never before encountered such personal angst and internal struggle over a perceived conflict between one’s worldview and science.”

The science behind science denial

The rejection of science takes many shapes, and Sinatra is a pioneer in classifying and pinning them down like exotic moths and butterflies. She and psychologist Barbara Hofer of Middlebury College are currently working on a comprehensive book for educators and communicators about the psychology of science resistance, doubt and denial.

Other books — notably Chris Mooney’s best-selling The Republican War on Science and Andrew Shtulman’s Scienceblind — have spotlighted aspects of the phenomenon. But Sinatra and Hofer’s forthcoming volume will be the first to flesh out a broader picture of psychological influences and suggest teaching strategies to mitigate the problem. (The project builds on their 2016 article, “Public Understanding of Science: Policy and Educational Implications,” in Policy Insights from the Behavioral and Brain Sciences.)

Sinatra has previously edited two books, written dozens of book chapters, co-authored more than 60 scholarly papers and delivered nearly 200 conference presentations in educational psychology. She joined the USC Rossier faculty in 2011 and served as associate dean of research from 2016 to 2017. Her own scholarship is headquartered in USC’s Motivated Change Research Lab, where a team of doctoral students and postdocs are helping Sinatra peel back the cognitive, motivational and emotional processes that lead to attitude change, conceptual change and successful STEM learning.

The learning platforms they study have come a long way since Sinatra hit a wall with that text about evolution 20 years ago. An intriguing project now underway at the La Brea Tar Pits, for example, investigates how different kinds of smartphone-based augmented reality experiences might lower emotional barriers to science learning in an informal public setting.

In collaboration with Benjamin Nye, director of learning research for USC’s Institute for Creative Technologies, Sinatra’s team recently piloted a five-minute prototype featuring an animated baby mammoth trapped in the oozing asphalt. Its mother approaches but cannot free her calf. The panicked pachyderms’ cries eventually lure some opportunistic dire wolves into the deadly pool. The pilot, completed last fall and tested with 60 visitors, was conducted to set the stage for a three-year collaboration with the La Brea Tar Pits and Museum that breaks new ground in measuring the learning and engagement value of an arsenal of emerging 3D tools and techniques (see “Re-Living Paleontology” on page 11).

Who’s in denial?

Sinatra doesn’t have direct expertise in evolution or climate change, but she has thoroughly educated herself on the big issues that seem to stoke the most egregious science denial. Religious fundamentalists, she notes, don’t have a monopoly on rallying around spurious facts. The tendency crosses belief systems and party lines. “Anti-vaccination and anti-GMO groups are progressive left, while the anti-climate change, anti-evolution movement is very much on the political right,” she says.

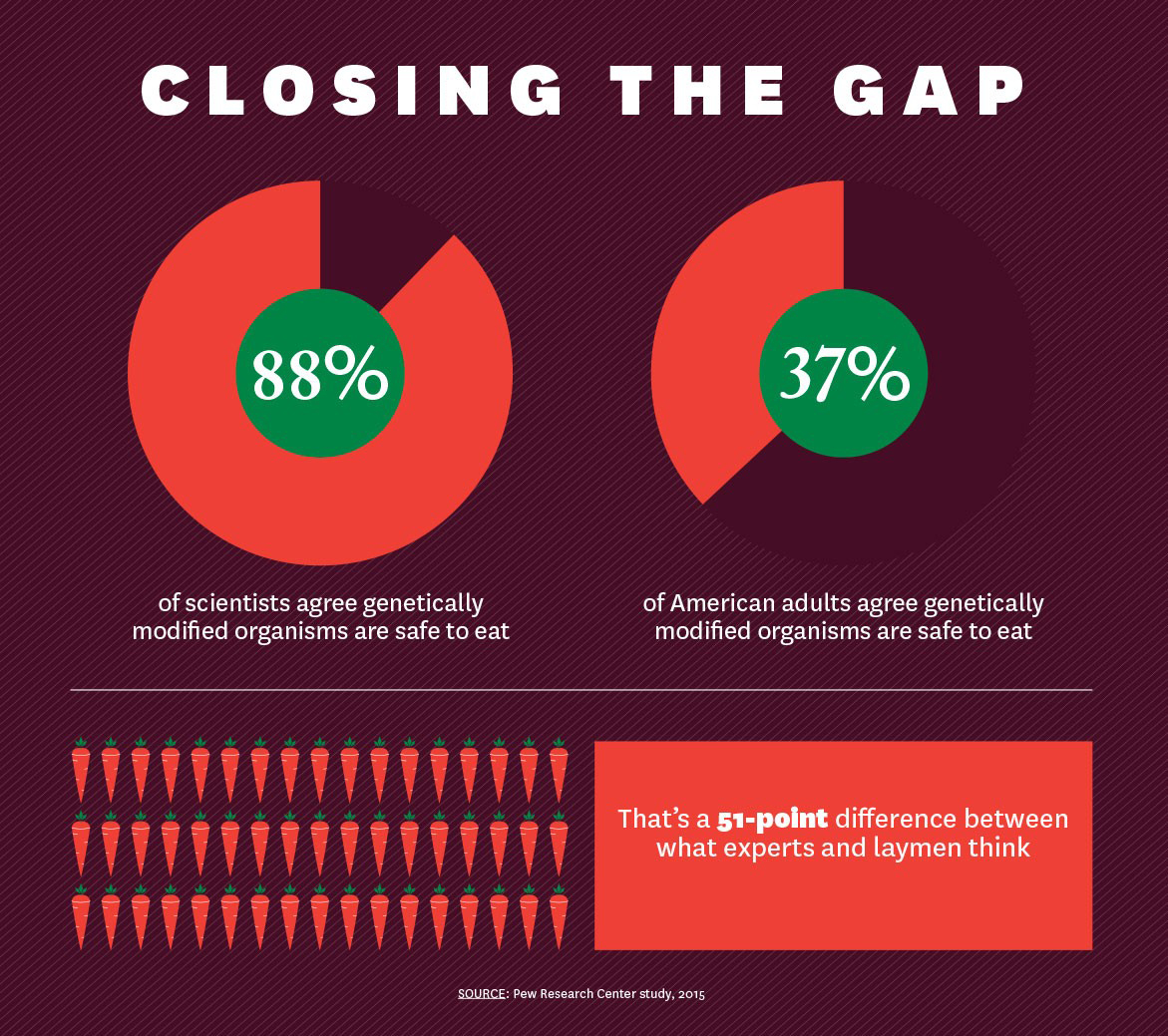

The statistics are stark. A 2015 Pew Research Center study found that while 88 percent of scientists agree genetically modified organisms are safe to eat, only 37 percent of American adults hold that view. That’s a 51-point difference between what experts and laymen think.

Nearly two centuries after Charles Darwin’s fabled voyage on the HMS Beagle, the statistics on views of evolution aren’t much better. Despite a 98-percent scientific consensus, only 65 percent of Americans believe humans evolved over time: a 33-point gap.

Sinatra attributes these glaring disconnects between thoroughly documented scientific evidence and contemporary popular beliefs to several factors — among them, a general erosion of trust in experts; new levels of scientific hypercomplexity that make it virtually impossible for laymen to independently assess the validity of expert claims; and a mass media propensity for “balanced reporting” that misleadingly places rigorously tested results on an equal footing with quackery and conspiracy theory-mongering.

The internet’s powerful information democratizing and tunnel-building effects only compound the problem.

Resistance triggers

The roots of resistance to scientific evidence are complicated, according to Sinatra.

“There isn’t one simple thing,” she says. “It’s values, community, identity, vested interest, to name a few.” Coal miners, with their livelihoods at stake, might have a strong financial incentive to reject evidence for human-induced climate change. Sinatra’s Utah study, where she exposed the faithful to a “refutation text” at odds with their creationist worldview, is an example of identity fueling resistance to science.

With so many possible causes, there can be no one-size-fits-all fix. To make inroads with resistant learners, science educators need to be curious and nimble. “It’s important to understand what the nature of resistance might be, where it stems from, in order to craft a message that would be better received,” Sinatra concludes.

Breaking through

Combating science denial requires what Sinatra calls a “hat trick.” First, overcome misconceptions with facts. Next, turn the negative emotions associated with those unwelcome facts into positive ones. And finally, familiarize everyone with the logic of the scientific method.

“When these three things happen, you see change in people’s attitudes,” she says. The landscape has changed since Sinatra’s reading study at the University of Utah sparked unexpected anger and pushback from its students, who were predominantly followers of the Church of the Latter Day Saints (LDS). Today, LDS does not take a position on biological evolution, and the LDS community includes many science teachers and active scientists.

Educators can leverage that kind of change to promote learning. Sinatra recently collaborated with a colleague on workshops to help biology teachers in West Texas feel comfortable teaching evolution even if their religious beliefs did not support evolution. Another joint project through Arizona State University has self-identified Christian biologists discuss their faith with their students and explain how they are able to strike a balance between religion and science.

“When I started this work,” Sinatra says, “we did not know much about the motivational factors in understanding science.” To change a flat-Earther’s mind, it was assumed that merely explaining the day-night rotation cycle and seasonal change would do the trick.

“Now we know it’s not that simple. Plenty of people still think the Earth is flat. It really doesn’t have anything to do with the science. It has more to do with psychology, which I find utterly fascinating.”