During a lesson in January exploring the principles of Athenian democracy, Rachel Davey, a teacher at City Heights Preparatory Charter School in San Diego, explained to her sixth-grade class the meaning of the word “democracy.” The word comes from two Greek words, she said: demos, meaning “the people,” and kratia meaning “power or rule.”

Rule by the people.

The students—a group overwhelmingly made up of refugees—took in her words. Some nodded. Others scribbled details on their sticky notes and whispered in their partners’ ears.

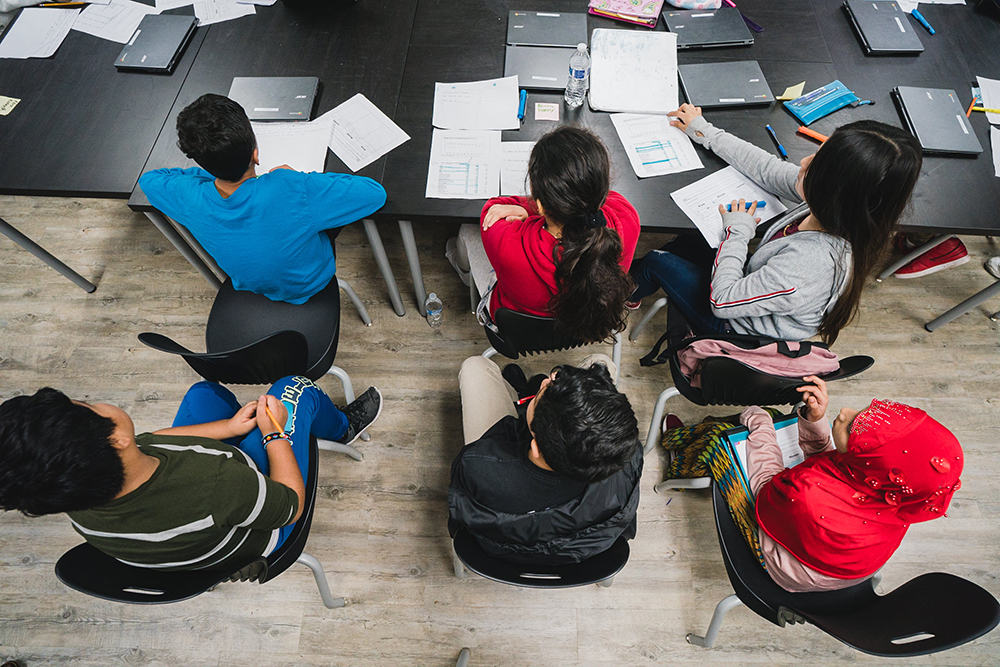

The students in Davey’s class work at shared tables. In fact, you won’t find individual desks arranged in neat rows anywhere within City Heights Prep. The classrooms are designed to foster collaboration and facilitate discussions among students.

And when a Socratic seminar is on the agenda, as it was in Davey’s class on Jan. 21, all of these tables are pushed into the center of the room. For these text-based discussions, the students gather round the single, central table, seated in two rows. The inner row is made up of the “pilots,” the speakers during the seminar. Behind them, in the outer row, are the “co-pilots,” who listen closely to the discussion. They take notes and quietly pass back their questions and observations about the subject at hand to the pilots.

City Heights Prep, directed by Elias Vargas EdD ’17, uses Socratic seminars in all of its levels, grades 6 through 12.

Socratic seminars are a sort of representative democracy in miniature. The pilots are the voice, the co-pilots are the body politic.

Some students, like senior Abdirizack, prefer to be a pilot. “It makes you feel like you’re more engaged and involved in the process,” he said. Abdirizack, a Somali Bantu refugee born in Kenya, has been at City Heights Prep for seven years.

Others, like junior Hinda, an Ethiopian refugee, would rather be the co-pilot. “Sometimes I’m too scared to say something. I feel like it might be wrong,” she said. “But if I have someone [to work with], I write it down and pass it to her and she [can] agree with me if it’s a good idea.”

Socratic seminars are a sort of representative democracy in miniature. The pilots are the voice, the co-pilots the body politic. Each role is valued equally: Listening is just as important as speaking.

There are no right or wrong answers in Socratic seminars. Differing opinions are encouraged, and some students are instructed to gather and present evidence for a viewpoint with which they don’t personally agree. Unlike traditional debate teams, where students memorize information and recite it at speeds indecipherable to the average ear, the Socratic seminar encourages engagement from all students in the discussion—both those speaking and those listening.

But before a class can even begin to participate in a Socratic seminar, it’s essential for students to consider their peers’ voices as “something they want to hear,” Davey explained. Without this environment of mutual respect, where everyone’s voice matters, the Socratic seminar, like democracy, will not function properly.

IN EMMA LAZARUS’ famous poem, “The New Colossus,” her “Mother of Exiles” stands at “sea-washed, sunset gates,” and welcomes tired, poor and huddled masses “yearning to breathe free.” These words, inscribed on a bronze plaque on the pedestal of the Statue of Liberty—one of the most recognizable visual icons of Western democracy—have long served as America’s promise to immigrants, asylum seekers and refugees, even if current policies and laws do not align with this vow.

But within the walls of this small charter school in City Heights, a community on the east side of San Diego, the promise spoken by Lazarus’ “Mother of Exiles” is kept. The student body at City Heights Prep is roughly 85 percent refugee. More than 30 languages are spoken among the 150 pupils, and students interact freely with one another. Bullying is largely absent, and the annual potluck day where students bring dishes from their native countries is one of their favorite events of the year.

Bereket, a junior whose family emigrated from Ethiopia as refugees, said, this “tight-knit [community] is different from traditional schools,” and it has been life-changing for him. He has many groups of friends from a variety of backgrounds, and when new students arrive, they often fit in immediately.

San Diego County has historically welcomed refugees, and for many, City Heights has become a haven. Data compiled from the 2000 census estimates that City Heights’ population comprises residents from more than 60 countries, including Vietnam, Syria, Cambodia, Nicaragua, Honduras, Iraq, Ethiopia, Somalia, Laos, Mexico and Guatemala. This population is reflected at the school—and with it comes challenges, but also a cultural richness.

Most students who find their way to City Heights Prep initially hear about the school via word of mouth—admission is free and open to all. When students arrive, many are learning English, and many come from socioeconomically disadvantaged backgrounds or from experiences of war. Students have what Vargas describes as “interrupted education.” One group of teenage boys from Syria had spent months in a refugee camp before finding their way to City Heights Prep. During their time at the camp, Vargas said, the only formal schooling the boys received was an hour of Arabic each day.

When Vargas was appointed director in fall 2018, the school was housed in a church, and only a small percentage of students were meeting state standards. Since then, Vargas has overseen the relocation of the school and hired new staff—including a full-time counselor to address students’ academic and emotional needs—and test scores have increased significantly.

In 2016–17, 13.2 percent of City Heights Prep students met California’s standards for English language arts and only 8.2 percent for math. By 2018–19, those numbers had risen to 38.5 percent and 20.8 percent, respectively.

Impressive, to say the least.

Although Vargas is proud of this metric (after all, test scores are an unavoidable circumstance of the current education system and the way California measures a school’s success), he is adamant that he is not just concerned with graduating students with high test scores. Just as essential, he said, is graduating good citizens who appreciate diversity and will “embrace and develop their talents to engage with the world.”

WHEN VARGAS WAS CONSIDERING taking on the role of director of City Heights Prep, he was specifically drawn to working with this unique population of students. As he weighed options on how the school’s curriculum should be structured, he decided to embrace and implement the principles of AVID—Advancement Via Individual Determination. The San Diego-based nonprofit offers a suite of resources—from professional development for educators to lesson plans and other classroom activities—that are focused on closing the opportunity gap. The Socratic seminar is one such classroom activity, and it’s an exemplar of how an AVID school approaches its goal of preparing students for life after they graduate. It encourages students to communicate positively, listen actively and take focused notes. It asks students to think outside the textbook and engage in their own inquiry. It asks them to see themselves in what they are studying.

Vargas finds the AVID approach especially useful for underrepresented students and English-language learners. And there’s data to support this. According to figures from the National Student Clearinghouse, 2016–2018, and AVID Senior Data Collection, 2010–2012, first-generation and low-income students who graduate from high schools where AVID is a part of curriculum are four times more likely than their peers to graduate from college within six years.

The ability to apply an approach like AVID to an entire school was one reason that Vargas was attracted to the position. Before City Heights Prep, he had never worked in a charter school. He held a variety of roles—from basketball coach and social studies teacher to high school principal—in the El Rancho Unified School District in southeastern Los Angeles County. But while City Heights Prep does not have all the resources that come along with a large school district—things like IT and HR departments—the school is able to make decisions swiftly and institute changes to benefit students.

Elias Vargas, EdD ’17, is not just concerned with graduating students with high test scores. Just as essential, he said, is graduating good citizens who appreciate diversity and will “embrace and develop their talents to engage with the world.”

OUTGOING. EMPOWERING. Progressive. Serious. Knowledgeable. Passionate. These are some of the words that Assistant Director Mrs. Mohammed—who came to the U.S. as a refugee from Iraqi Kurdistan—and school counselor Amanda Graceffa used to describe Vargas. Michael Watts, board chair of City Heights Prep and a first-generation college student himself—describes Vargas as “a pro” and “a great leader.” When Watts and the rest of the search committee were evaluating candidates to lead the school, they were “looking for someone who could apply really sound educational principles and orthodoxy to a very diverse [student body]” and could take the school to the next level. Vargas fit the bill. He also encourages professional development and gives his staff the space to be creative and incorporate new ideas.

When speaking of his philosophy of education, Vargas refers to a famous Albert Einstein quote: “Everybody is a genius. But if you judge a fish by its ability to climb a tree, it will live its whole life believing that it is stupid.” Vargas believes exposure to possible career paths—from app developer to attorney—can help students find a calling they will excel at and enjoy.

Through a grant from the nonprofit Project Lead the Way, the school offers multiple PLTW courses including, Computer Science for Innovators and App Creators, which shows students who love playing games on their phone what it might be like to develop them instead. Through courses like this one, students are exposed to what a career path could entail. And while some might learn they love creating apps as much as playing on them, others will realize this is not the right path for them.

This exposure, Vargas believes, is essential in helping students form their identities—not only for their own personal fulfillment, but also so they can contribute positively to their communities.

JON MORRIS, a lawyer-turned-educator at City Heights Prep who teaches 11th- and 12th-grade courses like Language of Law and Public Policy, says education should help “prepare students who can engage in a democracy.” But what are the tools required for engaging in democracy?

If a populace is to elect officials to represent them—from school board members to the president of the United States—it’s important to be equipped with the ability to think critically about issues and to engage in deliberation with fellow citizens.

Morris asked students to prepare legal memos that examined President Donald Trump’s now-infamous phone call with Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky. The students worked in groups of three to examine the call and make a determination on whether Trump violated federal law. Hinda explained, “We were studying our leader doing something he shouldn’t.” She enjoyed the project.

Many of the students come from nations where civil wars rage, and where democracy either doesn’t exist or is in tatters.

Some have witnessed its unraveling.

Kun, a senior who said “being highly informed” is essential to being a good citizen, is originally from Cambodia. After years of civil war and turmoil, the nation’s fragile democracy is threatened, despite international intervention. Media freedom—to name just one essential ingredient to a functioning democracy—has been “further curtailed,” a 2019 Human Rights Watch report found.

Another assignment asked students to select a law they believe to be unjust or one they would like to see enacted, and write a paper asserting their position. Topics ranged from overturning the law forbidding people from feeding homeless individuals to banning single-use plastic bags.

The project, however, will not end with their papers. The students, again working in teams, will identify and reach out to organizations sympathetic to their cause. They’ll then contact their local representatives and advocate for seeing the legislation overturned or rewritten.

The students at City Heights Prep are learning that democracy is ultimately a practice. It requires engaged citizens to participate and help shape the rules that govern them. It is not static. As the needs of the people who make up the democracy change, so must the democracy that represents them.

Democracy requires respect and equity to flourish, and the students at City Heights Prep understand these fundamental principles—perhaps because they know what it means to live without them.

AS I SAID GOODBYE to the students at City Heights Prep, Bereket and the other upperclassmen I spoke with asked if I could “give a shout-out” to Mr. Chalabi, the school’s meals and facilities coordinator. Mr. Chalabi, Bereket said, does so much for the students: He prepares their meals, fixes anything that’s broken, cleans the school and coaches after-school soccer. The students recognized and appreciated his essential role at the school. Democracy requires respect and equity to flourish, and the students at City Heights Prep understand these fundamental principles—perhaps because they know what it means to live without them.