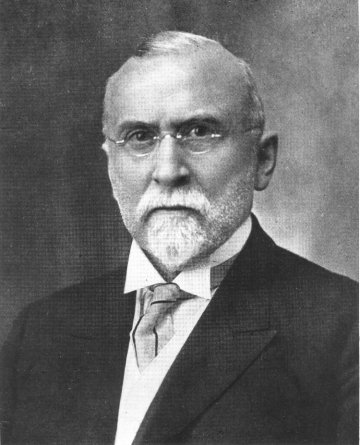

Headlined “USC Gets an Authority,” the June 16, 1909, article in the Los Angeles Times reported the hiring of a new professor: Thomas Blanchard Stowell, the longtime principal of a teacher training institute in Potsdam, N.Y., would head the education department at the University of Southern California.

The distinguished Stowell arrived at an opportune time. Los Angeles was booming and so was the demand for public education.

Over the next few years, he expanded the department’s offerings and waged a successful campaign to enroll aspiring high school teachers. Before long, education students were overwhelming the cramped facilities of USC’s College of Liberal Arts, leading university trustees to the step Stowell had been driving toward since his arrival.

In 1918, the university separated the department from the college and created the School of Education, with Stowell as its first dean.

Stowell would only serve a year because of health problems, but the school he launched celebrates its centennial this year. Known as the USC Rossier School of Education since 1998, it has left its mark on Southern California, supplying districts with thousands of teachers and administrators of every rank.

Over its long history, the oldest graduate school of education in Southern California has experienced triumphs as well as trials; great expansion as well as contraction; and spurts of bold innovation as well as struggles to adapt amid dramatic social and cultural changes in the communities beyond the university’s gates. Along the way it built a reputation as the state’s premier training ground for future education leaders.

More than 200 USC graduates have run California school districts, including more than 70 current superintendents. Trojans occupied the Los Angeles superintendent of schools office almost continuously for 50 years, from 1929, when Frank A. Bouelle BA ’12 stepped into the job, until 1987, when Harry Handler MS ’63, PhD ’67 retired. The 11th and most recent USC-trained educator to hold the job was Michelle King EdD ’17, who served from 2016 to 2018.

The school also has produced leaders at the county and state level, such as Max Rafferty EdD ’56, the state superintendent of public instruction in the 1960s who was known for his conservative, back-to-basics approach.

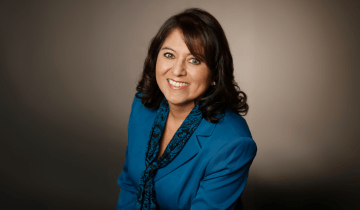

“We were preparing leaders who knew good organizational theory and good business practices,” said Karen Symms Gallagher, Emery Stoops and Joyce King Stoops Dean of USC Rossier. “So almost immediately, while we were preparing teachers we also were preparing principals and superintendents.”

Emergence of a city and a new school of education

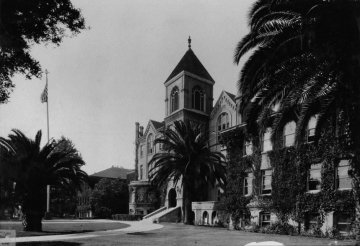

The story of USC Rossier can be traced back to 1880, when USC opened with no endowment, three full-time professors and a classics-oriented curriculum that included a single course in pedagogy. Los Angeles was then a dusty frontier town of 11,000 without paved roads, electric lights or telephones—“Queen of the Cow Counties,” its snooty neighbors to the north called it. USC’s three businessmen founders recognized Los Angeles’s potential and created the university to provide the doctors, lawyers, dentists and other professionals that the emerging city needed to thrive.

As the population expanded—it would reach 50,000 by 1890 and more than 500,000 by 1920—Los Angeles would also need teachers.

The Los Angeles State Normal School, which had opened in 1881, was the only local option for aspiring grammar school teachers. By 1912 it had 900 students, the largest enrollment of any normal school in the country, according to a 2015 history by Keith Anderson. Seven years later, the state would turn it into the Southern Branch of the University of California—UCLA.

For USC, which in its early decades was constantly on the brink of financial collapse, a teacher training program would fill a community need and bring the university the crucial tuition dollars that helped keep the doors open. The School of Education quickly developed a larger enrollment than any of the university’s other professional schools, including those for medicine, dentistry and law.

Although the university had established a pedagogy department in 1896 under James Harmon Hoose, no one appeared to be teaching the subject when Stowell arrived; according to the 1909 USC El Rodeo yearbook, the versatile Hoose was teaching philosophy and history, with no mention of pedagogy. Stowell not only revived the flagging department but led an effort that, just two years later, brought USC a key distinction: the authority to recommend graduates for the high school teaching credential.

“That was a huge achievement, not only for the education department but for the university,” Gallagher said. “USC became the first institution in Southern California and the third in the state certified to offer the credential. In this respect, it put USC on an equal footing with Stanford and the University of California, and it raised the university’s status at a time when its future was still far from assured.”

Forging partnerships with Los Angeles schools

The school’s close partnership with Los Angeles city schools was evident in the years leading up to World War I, when a surge of immigration from Europe and Mexico began to fill classrooms with non-English-speaking students. Under Stowell and his long-serving successor, Lester Burton Rogers, many of the school’s faculty and graduates helped shape and implement methods for “Americanizing” the newcomers.

Critics of the Americanization movement would later blame it for the rise of segregation and ability grouping, which relegated Mexican children in particular to a less academic curriculum than was taught to Whites. At the time, however, the efforts of USC graduates like Albion Street School Principal Grace Turner MA ’23 and Macy Street School Principal Nora Sterry BA ’20, MA ’24 were widely praised as effective and progressive in the mode of John Dewey and Jane Addams.

Sterry, in fact, was lauded as a hero by the Mexican immigrant community around Macy Street during the plague of 1924, when she defied a quarantine order to take care of sick families. Her school, located in present-day Chinatown, was considered a model of reform for pioneering low-cost school lunches, health screenings and other now-standard features of public schools.

“The cadre of Progressive-era teachers and reformers who came out of USC, many of them women, played important leadership roles in the education of some of the city’s poorest and most vulnerable citizens,” said USC Prof. William F. Deverell, who directs the Huntington-USC Institute on California and the West. “We might fault them for some of their views on race and Americanization, but, at their best, they worked on the front lines of humanitarian and educational reform.”

USC’s education school, like the rest of the university, had little racial and ethnic diversity until much later in its history. Among those who helped break the color barrier were Hazel Gottschalk Whitaker and Verna B. Dauterive.

In 1931, Whitaker earned a master’s degree in education from USC with a study of gifted black children in the L.A. school system, which found that Black and White children from the same social class and geographic area had similar IQs. In 1936 she became one of the first three African Americans to teach at the secondary level in Los Angeles. She taught the district’s first class in “Negro history” at Jefferson High School, according to historian Judith Rosenberg Raferty.

In 1943, Dauterive became, at 21, the youngest teacher in the Los Angeles school district and one of only four African Americans then assigned to classrooms. Studying nights and weekends at USC, she earned a master’s degree in 1949 and an EdD in 1966 with a widely cited dissertation on the history of integration efforts in L.A. public schools.

Later she and her husband, financier Peter Dauterive, funded USC Rossier’s first scholarship for doctoral students of color. After his death, she donated $30 million to USC to build the Verna and Peter Dauterive Hall, an interdisciplinary research and teaching center that opened in 2014.

As school boards became more professional, they increasingly relied on university-trained experts to help solve problems. One of USC’s most sought-after education experts in the 1930s and 1940s was Osman R. Hull, who conducted an influential study of the Los Angeles school district’s central administration at a time when its top management was dogged by allegations of corruption.

“Organizationally, the system was, in a word, a shambles,” future USC education professor Leon Levitt wrote in his 1970 doctoral dissertation on the early history of the School of Education.

The Los Angeles school district was a case study in dysfunction. In the early 1930s it had four administrative heads instead of one, with the superintendent, business manager, auditor and secretary of the board all reporting directly to an overwhelmed Board of Education. To free the board to focus on policy instead of minutiae like teacher assignments and the price of chalk, Hull and USC colleague Willard S. Ford proposed empowering the superintendent to oversee day-to-day operations and the other administrators in the central office.

They also urged the board to create the jobs of deputy superintendent and six assistant superintendents who each would oversee a region of the 360,000-pupil district.

The board began putting the key changes into effect in 1934, creating the management structure that has been in place ever since.

“That’s what the flow chart looks like right up to today, with the superintendent handling all the administration,” said former Los Angeles Unified School District Supt. Sid Thompson, who headed the district in the 1990s. “I’m really surprised that it started that far back. Before this happened, the board must have found itself in a real mess.”

Hull went on to become the fourth dean of the School of Education, serving from 1946 to 1953. His co-author, Ford, left USC to work for the Los Angeles school district as an assistant superintendent in charge of the reorganization.

A rise to national prominence in the Melbo years

Ford’s departure created a faculty opening for Irving R. Melbo, who became one of the most influential deans in the school’s history.

An expert in educational administration, Melbo was hired in 1939 and rose to dean in 1953. He created EDUCARE, an influential professional support group that raised tens of thousands of dollars for the school, and oversaw the building of Waite Phillips Hall of Education, named after the Oklahoma oilman whose bequest funded the construction.

He also sent USC education professors to teach U.S. military personnel and their dependents at U.S. bases in Europe, Asia and Africa, a lucrative effort that resulted in the awarding of 800 master’s degrees overseas before the programs were phased out in the 1990s.

“The sun never set on USC—we were all over the place,” recalled Myron Dembo, a professor of educational psychology who joined the faculty in 1968.

Melbo’s greatest impact was in vetting graduates for top school district jobs throughout California.

“When I received my degree, USC was the only game in town if you wanted to be a superintendent,” said Clinical Professor Emeritus Stuart Gothold EdD ’74, who in 1979 became the third consecutive Trojan to serve as superintendent of the Los Angeles County Office of Education.

As a graduate student, Gothold helped Melbo keep track of job openings on a map in a basement office. “I ran it for a short while, against my will,” he recalled. “Melbo was a strong individual who surrounded himself with strong people in the field. Like an old boys club, if you will.”

“It was really under Melbo that the school attained national prominence,” John Orr, a religion professor who served as dean through most of the 1980s, said in a 1998 interview.

But the Melbo years also stoked concerns that the school wasn’t paying enough attention to its primary purpose—improving public education in California, particularly in tough urban environments like Los Angeles.

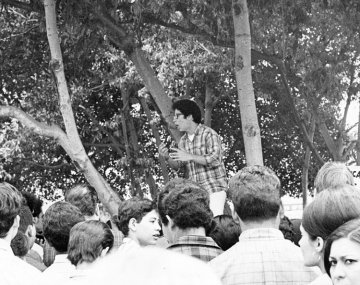

His tenure coincided with the 1965 Watts riots and the 1968 East Los Angeles “blowouts,” in which 20,000 students abandoned their classrooms over unequal opportunities for Latinx students. “There was little focus by the school on the riots, discrimination, inequity,” said Dembo, who retired in 2009 after 41 years on the faculty. “We were … doing some good things, but that didn’t permeate the school of education in terms of its most important mission.”

Renewing the commitment to public education

The school began to change direction under Guilbert C. Hentschke, who was dean from 1988 to 2000. He hired Reynaldo Baca from Cal State L.A., where Baca ran a program to help bilingual classroom aides earn teaching credentials. According to Baca, who went on to direct the USC Latino and Language Minority Teacher Project for two decades with Associate Prof. Michael Genzuk, 1,300 aides received bilingual credentials and about 36 later became principals or earned doctoral degrees.

Hentschke also hired William G. Tierney, who co-directs USC Rossier’s Pullias Center for Higher Education—the only endowed center of its kind in the country—and Estela Mara Bensimon, Dean’s Professor in Educational Equity, who in 1999 founded USC Rossier’s Center for Urban Education. Both are specialists in college access for underrepresented groups, particularly Latinx, African American and low-income students.

To the dismay of many alumni in the field, the school under Hentschke also began to prioritize scholarship over practice, a tension in most university education schools at one time or another. In addition to Bensimon and Tierney, whose research has landed them on Education Week’s annual rankings of the nation’s most influential education scholars, Hentschke hired nationally known experts in school finance and governance who were strongly focused on the challenges facing large urban districts.

Mission driven

The Hentschke era drew to an end with two major events—one a cause for celebration and the other for dejection. Each would shape the school’s future.

The first was the announcement in 1998 of a $20 million pledge from Barbara and Roger Rossier, who earned doctorates in education at USC and founded a successful string of schools for the learning disabled.

Their gift—the largest ever pledged to an education school in the U.S. at a time when few had such generous benefactors—couldn’t have come at a better time.

“It helped in some ways to save the school,” Hentschke said recently. “Now, named [education] schools are a dime a dozen, but they weren’t back then.”

In the 1990s, the university under President Steven Sample was laboring to join the ranks of the nation’s top research institutions. Some of USC’s schools were feeling the heat. “There was some talk of ‘Do we need a school of education?’” Dembo recalled. “You were going to be left behind if you didn’t shape up and go with the mission of the university.”

So, in 2000, when the school received a scathing evaluation by an academic review panel that included experts from other universities, it didn’t bode well. Among the shortcomings cited in the final report were too many mediocre students, a dispirited faculty with few nationally recognized research leaders, the lack of a coherent vision for the school, and an EdD program that was outdated and indistinct from the PhD program.

Gallagher was still education dean at the University of Kansas when she received a copy of the report. “The president and the provost both indicated one of the options after the review was to close the school,” she recalled. “I said, ‘Of course, but I’m not the person to do it.’ I thought there were enough good things to turn around.”

Soon after she joined USC Rossier, she mobilized faculty, staff and students to collaborate on a new mission statement focused on improving learning in urban settings. The PhD program was geared to research and academic careers, while the EdD was revamped as a three-year program for working professionals using research to address practical problems in urban education. The Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching praised USC Rossier’s approach to the EdD as a model for the nation.

After meeting those challenges, Gallagher led the school into new territory. In 2009 it launched the first fully online master of arts in teaching program in a major research university. In 2012 it opened USC Hybrid High School, a charter school in downtown Los Angeles with a predominantly low-income Latinx and Black enrollment that is now part of an expanding network run by Ednovate Inc., the charter management organization started by USC.

Hybrid High has attained a 100 percent graduation and college acceptance rate for its first three graduating classes, an impressive achievement and much welcomed by Gallagher and other USC leaders after a five-year partnership with LAUSD’s Crenshaw High School collapsed in 2012.

“It’s a big risk for a reputable school of education to take on such a challenge in the face of a school partnership that didn’t fully meet the dreams of all the project’s partners,” said Darnell Cole, who along with Shafiqa Ahmadi, directs USC Rossier’s Center for Education, Identity and Social Justice, and is tracking the progress of Hybrid High’s graduates. “The real challenge is having the commitment to stay connected.”

As USC Rossier marks its milestone birthday, Gallagher contemplates the challenges ahead, especially how to attract the best students when more affordable options abound. The success of its charter school experiment may help.

“There is a lot of data showing that what we are doing at Hybrid High is making a difference,” Gallagher said. “I think we have managed to prove that, through our research and our practice, a school of education can be relevant.”

In 1969 historian and USC law school graduate Carey McWilliams wondered if the university would “adjust to the new realities that swirl about it in a community that has become synonymous with rapid change.” Nearly half a century later, USC Rossier faculty still grapple with that question as they look toward the future.