Graffiti-covered walls, trash-strewn hallways and gun-toting Black and Latino students who are so violent that they bash open the head of a White teacher on the cafeteria floor during lunchtime.

That’s the infamous beginning of the 1989 movie Lean on Me—and in case viewers don’t feel scared enough by the visual onslaught of buck-wild juveniles, it’s all set to the sonically jarring screams of Guns N’ Roses front man Axl Rose belting out “Welcome to the Jungle.”

What does it take to turn around such an out-of-control school? In the film, bullhorn- and bat-wielding Eastside High principal Joe Clark, portrayed by Morgan Freeman, relies heavily on campus security officers. In one early scene, Clark announces to the faculty that a newly hired dean of security “will be my avenging angel.” Soon thereafter, a small army of these officers escorts a bunch of teenagers whom Clark deems “drug dealers, drug users and hoodlums” off an auditorium stage and out of the building.

The film’s “based on a true story” depiction sent a clear message about what it takes to ensure safety and boost student achievement in a high school attended by students of color: zero-tolerance policies and a large law enforcement presence. America, it seemed, agreed. The film was a box office smash.

“Everyone needs to be safe in schools. No one can learn, nobody can work in an unsafe environment,” says Pedro A. Noguera, the Emery Stoops and Joyce King Stoops Dean of the USC Rossier School of Education, who has written extensively on racial disparities in school disciplinary practices.

However, the hiring by school districts of more police officers to patrol urban campuses serving mostly Black and Latino kids, Noguera says, “was always tied in with the idea that these schools were unruly and that you needed extra measures to ensure safety.”

Nowadays, that seems to mean keeping schools safe from 6-year-olds who are having a terrible, horrible, no good, very bad day.

In February, body-camera footage released by the Orlando Police Department of the September 2019 arrest of Kaia Rolle went viral. The Black first-grader had thrown a tantrum because she wanted to wear her sunglasses inside the classroom.

It was important to perpetuate a narrative of Black people, especially Black students, being dangerous and having the potential to cause harm to White students. [Then] White parents could say, ‘It’s not about race. It’s about keeping my child safe.’” —Akua Nkansah-Amankra, USC Rossier PhD candidate

“I don’t want handcuffs on, no, don’t put handcuffs on,” Kaia sobbed on the video. “Help me, help me, please, help me,” she cried.

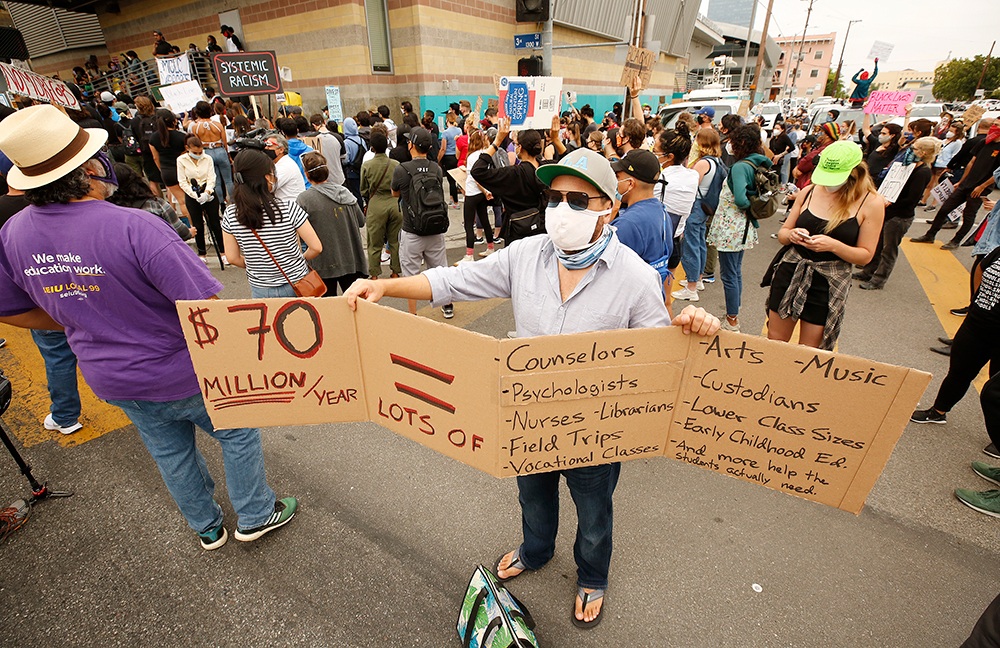

In the aftermath of nationwide protests and calls for defunding the police, following the killing of George Floyd at the hands of law enforcement officers in Minneapolis, students, parents, teachers and community members are fed up with the arrest-a-Black-first-grader approach to school safety. Instead, they’re demanding that school boards reevaluate the use of police in schools, and in some cases, cancel contracts with police departments altogether.

“‘Defund the police’ is a starting point for reconsidering how we address security in schools,” Noguera says. “We should ask, ‘What supports do those schools need?’ In L.A., we have a 500–1 counselor-to-student ratio. Let’s address that. Let’s get more counselors, more social workers. In neighborhoods where there are issues of safety, let’s work with police to ensure kids can get to and from school safely. But their job is to protect, not to police the campus.”

How we got here

In 1999, two high school students—teens who did not fit the description of whom America had been taught to fear—forever changed schooling in the United States. Eric Harris and Dylan Klebold, White 12th-graders at Columbine High School in Littleton, Colorado, murdered 13 people, wounded 24 others and then turned their guns on themselves.

The epidemic of school shootings that started with Columbine got people scared, Noguera says. “So several states adopted zero-tolerance policies. And with the zero-tolerance policies, you started to see more districts bringing police in.”

What policing a campus looks like varies from school district to school district, as does who’s even doing the job. The most recent Indicators of School Crime and Safety report from the U.S. Department of Education defines school security staff as security guards, security personnel, school resource officers (SROs) or sworn law enforcement officers who have a presence in schools.

Adrian H. Huerta, an assistant professor of education at USC Rossier, says he published research in 2019 about the kind of violence that Latino boys experience in schools, and a consistent theme emerged: the role of school resource officers.

“Often, they’re the perpetrators and instigators who push boys of color to react,” Huerta says. “From what the students shared, school resource officers would provoke them and call them out to elicit a response. So what happens when you’re 16 or 17, getting called out in front of friends? You respond. And then what happens? You get arrested. And then what happens? You go to juvie. And then you have a record.

“It’s the perfect storm to get them on that school-to-prison pipeline,” Huerta says.

The very first standardized, districtwide SRO program began in the 1950s in Flint, Michigan, says Akua Nkansah-Amankra, a PhD candidate and research assistant at USC Rossier whose areas of focus include school discipline, restorative justice and critical race theory. However, she’s found that records going back as far as 1939 show that major cities like Indianapolis and Los Angeles were using police officers in schools.

“From my research and what I know about police officers being used at that point in time, it seems like a huge part of that was around controlling students with disabilities,” Nkansah-Amankra says.

“The system of policing has always been used for people who are considered deviant in some ways,” she says. “For the longest time, it was considered absolutely normal to exert force on kids with disabilities.”

Around the time when the Supreme Court ruled that segregation was illegal through the Brown v. Board decision, “it was important to perpetuate a narrative of Black people, especially Black students, being dangerous and having the potential to cause harm to White students,” Nkansah-Amankra says. Then, “White parents could say, ‘It’s not about race. It’s about keeping my child safe.’

“The popularizing of police officers in schools is directly tied to the Reagan era and the Clinton era,” Nkansah-Amankra adds. “Democrats and Republicans were basically competing with each other to see who would be the toughest on crime.”

In 1983, L.A. Police Chief Daryl Gates co-founded the Drug Abuse Resistance Education, or D.A.R.E., program with the Los Angeles Unified School District. The war on drugs-era initiative regularly brought into schools police trained under Gates’ aggressive, paramilitary-style leadership. Once on campus, officers talked to students about drugs using a zero-tolerance framework—they could even report to officers if a parent or guardian had any drugs in their home. Since then, D.A.R.E. has become a staple of schools nationwide.

To students, the work that an officer does in that setting—or even just standing in a hallway during a passing period—is very similar to what they do in the community. “Which is to remind them that they’re being surveilled. That they’re being watched,” Nkansah-Amankra says. Well-meaning people may want to see SROs or other security staff in schools as “Officer Friendly,” but “that hasn’t necessarily stopped cops from engaging in active violence against students,” she says.

After Columbine, school security “got more state and federal funding and focus,” Huerta says. And in the years after 9/11, additional funding for security personnel and military-grade weapons poured into districts. LAUSD made headlines in 2014 after public records revealed that the district had a mine-resistant ambush-protected (MRAP) vehicle made for combat in Iraq, as well as grenades, rocket launchers and assault rifles.

If it’s two kids fighting because someone made a pass at someone’s girlfriend or boyfriend or whatever, do we really need to call the police? Do we really need to cite them for assault or battery?” —Adrian H. Huerta, USC Rossier Assistant Professor of Education

“When I hear law enforcement agencies are collecting military weaponry, it makes me think they’re preparing for a war on the streets with young people,” Black Lives Matter co-founder Patrisse Cullors MFA Art ’19 told the Los Angeles Daily News. “If you are relating to students in K–12 as a potential criminal, then when you see them get into a fight in a school, instead of thinking, ‘This is a kid in a fight, they need to go to the principal’s office,’ they’re going to see a crime.”

“We have to ask, ‘What creates a safe and orderly environment?’” Noguera says. “And it’s not the presence of men with guns. In fact, it has the opposite effect. I see a bunch of people with guns, I don’t feel safe; I feel like, ‘Wow, why do we need so many men with guns here?’”

According to the Indicators of School Crime and Safety report, 61.4 percent of public schools said that during the 2017–2018 school year, they had one or more security staff members present at least one day per week. That’s up from 41.7 percent during 2005–2006.

The data also show that security staff are more likely to be concentrated in schools with higher minority enrollment. During the 2017–2018 school year, 67.4 percent of campuses where students of color were more than three-fourths of the student body reported having security staff.

In comparison, 58.3 percent of campuses where students of color were less than one-fourth of all students had security staff.

Racial bias in school policing

Noguera went to Columbine after the shooting and spent some time talking to the staff.

“How come no one noticed these boys in the trench coats and doing Nazi salutes?” he says he asked. The reply: “Yeah, we just thought they were strange. It didn’t fit our definition of what an at-risk youth was. They had good grades. They came from middle-class families.”

“So much of it is rooted in assumptions about where the threat lies,” Noguera says. “You look at the evidence. The people most likely to shoot up a school are White males. You don’t see Black males or females shooting up schools—or White females. But no one is targeting White males based on some profile.”

“We know there’s a racialized context to the presence of police in schools and how aggressive they are with students of color especially,” Huerta says. “I say Black and Latino, but it’s also Native youth. It’s also Southeast Asian youth. It’s also Pacific Islanders that bear the brunt of overpolicing in K–12.”

Indeed, Parkland, Florida, school shooting survivor and March for Our Lives co-founder David Hogg recently wrote on Twitter, “Putting cops in schools is a threat to school safety that endangers the lives of millions of black, brown and indigenous children.”

It’s not unusual to see news stories of what happens to children of color who interact with school resource officers or other security staff on campus.

In November 2019 at John C. Fremont High School, a majority-Latino campus in L.A., more than two dozen Los Angeles Police Department officers responded to a fight on campus by using pepper spray. This wasn’t the first time police had used the potent inflammatory agent on students. In June 2016, police responded with pepper spray to an altercation between students; at least 16 students and one officer were exposed to the spray.

“I was just in the crowd and the cops just started pepper-spraying everyone,” one bystander told reporters after the incident in 2016. “They pepper-sprayed, like, 30 kids.”

And in December 2019, footage of a school resource officer at Vance County Middle School in Henderson, North Carolina, also went viral on social media. The now-fired officer can be seen picking up and repeatedly body-slamming an 11-year-old Black boy to the ground.

“I don’t care what happened,” the boy’s grandfather, Pastor John Miles, told local reporters. “My grandson should never have been attacked by a grown man that we trust in law enforcement.”

“Study after study after study tells us school resource officers don’t work in schools,” Huerta says. “From the youth that I’ve interviewed, [SRO’s are] the ones body-slamming kids. They’re the ones spraying Mace in the cafeteria when there’s a fight. They’re the ones searching kids, grabbing them everywhere and trying to find a weapon when these kids have nothing on them.”

Students carry that anger with them, Huerta says, “and then they pop off in class.”

Most people “don’t realize how this results in criminalization,” Noguera says. “Kids are now being arrested for offenses that were never criminal before. An argument with a teacher gets heated. Next thing you know, a police officer is called. Then the child is being arrested for resisting arrest when it could have been de-escalated. It should never have gotten to that point.”

What does a safe school look like?

Historically, big school districts invest “millions and millions of dollars into campus police,” Huerta says. Instead of buying military-grade equipment, we have “an opportunity to reallocate those funds into education, into health care in the community and into other community service programs.”

So, what would an ideal school look like staffing-wise if that money went elsewhere?

Change can’t happen in a vacuum, Huerta cautions. “Instead of fixing the individual issues, we need bigger solutions—like bigger anti-poverty solutions,” he says. “How do we as a society really take care of and invest in people and families and community in a real way? I think those are bigger questions that schools cannot answer by themselves.”

That said, along with expanding the number of school counselors, “we need a social worker in every school or we need a social worker that rotates between two or three schools to build relationships,” Huerta says.

Or, what if master of social work students were put in schools? “I would love for it to be five or six interns,” he says, and they need to be a sustained presence at a school several times per week. Otherwise, “it turns into how school nurses might be at one school one day a week and that person is doing triage for kids all day.”

Keep in mind, Noguera says, “if the school is staffed by a bunch of adults who don’t know that community and who don’t understand the kids, then just bringing in counselors and social workers is not going to be good enough. They need to actually know the community where they are.”

Nkansah-Amankra says whatever staffing or policy changes are made, it’s critical schools use an intersectional, holistic approach. “Even when school districts change their policies to not use physical force against students—or they may reduce the number of incidents for which a student may get suspended for—oftentimes those rules don’t apply to students with disabilities,” she says. “Or there’s some kind of loophole that still makes it OK to use that type of force against them.”

You would have adults present on campus with—and this is the key—moral authority. … If they trust the adults, they’ll let them know, ‘There’s going to be a fight after school; someone should come talk to this girl because she's upset.’ The kids will tell you—that’s why I say safety is a product of relationships.” —Pedro A. Noguera, USC Rossier Dean

And, if that holistic, relationship-building approach isn’t taken, Huerta says, a social worker might just “interact with students and say, ‘Oh, this family is dysfunctional. Those kids need to go foster care.’ And then that changes the trajectory of these kids.”

“You would have adults present on campus with—and this is the key—moral authority,” Noguera says. “You need adults around that the kids will confide in. If they trust the adults, they’ll let them know, ‘There’s going to be a fight after school; someone should come talk to this girl because she's upset.’ The kids will tell you—that’s why I say safety is a product of relationships.”

And there are people in the community who can help.

“Typically, at a middle school, the security guard is a big man because the theory is you want someone who is physically intimidating to keep the school secure,” Noguera says. But at a middle school Noguera worked with in West Oakland, California, the school made an unexpected choice.

“This school decided to hire a 63-year-old grandmother to be the security guard,” he says. “And the reason why is because she had worked before as a parent liaison and they knew she knew the community, she knew the kids, she knew the staff. And so, they knew that was the kind of person they needed, not someone physically intimidating. I give the school credit for having the foresight to realize she could do the job. “That’s what I mean by moral authority,” he says. “You have to recruit with that kind of goal in mind—people who have that kind of connection to the community. That’s who you’re looking for.”

Huerta says we also need moral courage from school leaders and superintendents to set “very clear expectations of when to call school resource officers or school police or even a local police department.”

“If it’s two kids fighting because someone made a pass at someone’s girlfriend or boyfriend or whatever, do we really need to call the police? Do we really need to cite them for assault or battery? In the past it used to be like, go home for two days and cool off.”

The broader community also needs to have the moral courage to recognize that the way school resource officers and other security staff have interacted with students is not the answer—even if something horrible happens.

“All it takes is one incident—someone coming with a gun or someone getting shot,” Huerta says. “Or someone getting beat up really bad. One viral video will make parents pause and respond and be like, ‘Well, now we need police again, because look what happened at that school. Is my kid next?’”

“Fear should not guide our policies,” says Noguera. Instead, we need to “break the cycle of violence by asking different questions. That’s why I say you ask, ‘OK, where do we see safety in schools, and what makes those schools safe?’ It’s not about … [having] the best metal detectors and the biggest guards with guns.”