It is no surprise to many that the effects of “post-COVID” learning loss are still being felt today more than three years after schools were shuttered at the onset of the pandemic. While there is extensive research on this phenomenon, a new study from USC Rossier School of Education and USC Dornsife College of Letters, Arts and Sciences found an apparent gap between the concerns of experts/researchers and parents about the severity of these learning loss issues.

While it is difficult to definitively determine an exact date, post-COVID refers to the negative impact the pandemic has on education and learning. The duration and severity of school closures, the effectiveness of remote learning measures and the availability of resources for catch-up programs are a factor in determining when the post-COVID learning loss is addressed. USC researchers noted in the new study that parents and experts did not share the same level of concern regarding learning loss and sought to understand the reasons for this gap.

Key takeaways from the study:

- Collectively, caretakers did not express concern about their children’s academic well-being post-COVID

- Caretakers did not appear to think much about their child’s scores on standardized test post-COVID; whereas experts did

- Caretakers reported seeing problems caused by COVID, but often only among “other” children

- Caretakers believed that school and classroom expectations have been lowered

- Caretakers think children are resilient

Researchers Morgan Polikoff and Amie Rapaport have extensively written about the “parent-expert disconnect” in the past and have offered hypotheses and recommendations to mitigate the concern. While the disconnect may appear to be a purely academic issue, it can have important real-world consequences.

“As a research team that has led nationally representative surveys throughout the pandemic to understand and document these phenomena, we wanted to understand the disconnect issue in more depth,” said USC Rossier Associate Professor Morgan Polikoff, co-author on the study and fellow with the Center for Economic and Social Research (CESR) based at USC Dornsife.

Polikoff and Rapaport, a research scientist with CESR, co-authored “The Kids Are All Right? What Parents Really Think About How COVID Affected Children.” Leveraging the Understanding America Study’s (UAS) longitudinal panel, the report is based on 40 interviews with caregivers drawn from a nationally representative sample of households surveyed throughout the pandemic with school-aged children. Caregivers were asked about their children’s educational performance, their experiences during COVID and their own views on the broader phenomenon of COVID learning loss.

“The interviews gave us a very powerful window into what happened to American children during COVID, and what continues to happen to them as we all work together toward recovery,” said Rapaport.

Notable findings:

According to the study, most parents truly are not very concerned about their children’s academic wellbeing post-COVID

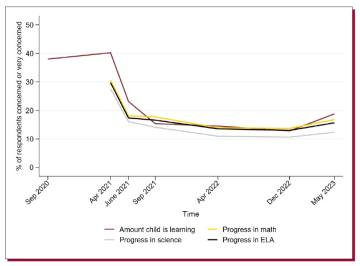

Earlier in the pandemic, approximately 30–40% of respondents reported concern about their students’ academics. Recent data from the UAS found only about 12–18% of respondents reported concern during the 2022–23 school year (See chart). The interviews shed light on why parents report low concern, despite declines in standardized test scores nationwide.

Some guardians shared statements like “Everything is fine. She’s on track socially, academically” and “teachers [went] above and beyond to be sure all students were grasping material and had individualized attention…students really benefitted.”

Conversely, some caretakers did express concern. Guardians described their child’s academic struggles over the past few years including depression and being socially withdrawn. One parent described 2020-21 as “a wasted year”. Parents said those hardships had eased over time, however, and that some learning issues had resolved once school returned to in-person classes.

These interview findings confirmed prior survey work showing that caretakers mostly think their children are doing well and are on track after COVID. While many caretakers noted various struggles that students experienced during COVID—social isolation, falling behind in particular subjects, fear of illness— guardians mostly felt that these concerns were in the past or that they soon would be.

A minority of parents are quite concerned—just as much about academics as social-emotional well-being—post-COVID

The researchers chose half of the 40 parents because they expressed concern on the most recent surveys. But when interviewed, the actual number expressing concern was even lower—just one-third.

However, the small group of parents in the study that did express concerns about their children’s academics often expressed additional concerns about their children’s social or emotional well-being.

Some of these parents observed that their children not only lagged in basic educational skills, but also faced challenges in emotional development. For instance, one parent reported their child feeling “very depressed to the point of wanting to take their own life” due to emotional distress induced by COVID.

Most caretakers think experts’ concerns about child well-being overall are not overblown

In contrast to their feelings about their own children, the study found that parents and guardians were concerned about the impacts of COVID on children more broadly. Parents were asked if they had heard—either in the news or in social media—about how children in the U.S. are doing now compared to before the pandemic.

Before hearing a description of the learning-loss phenomenon, approximately half of the interviewees reported hearing of learning loss, listing sources like the news, local teachers/school leaders, a religious magazine and social media. The findings suggest that COVID learning loss is a widely known phenomenon.

Next, interviewees were read a brief statement from U.S. Secretary of Education Miguel Cardona that described the phenomenon. After that, two-thirds of parents felt the learning loss concern was not overblown. Some of them simply trusted the reporting and believed the arguments of experts, while others reported that they had seen the damage of COVID in one form or another.

Why then is there a parent-expert disconnect?

The study demonstrates that a small proportion of parents were concerned about the impact of COVID on their own children. But experts have expressed much greater concern, focusing on trends in student test scores, attendance and other measures of engagement. The report sought to probe the reasons for this apparent disconnect.

- Caretakers don’t think much about test scores; experts do

According to this study’s interviews, when it comes to judging student performance, caretakers relied on grades, other school-reported measures of student progress and their own observations of their children’s work and work ethic, rather than standardized test scores.

Only five of the 40 caretakers who participated in the study mentioned their child’s performance on standardized tests, while all mentioned grades (on assignments, on class tests, on report cards). Standardized test results were not salient considerations regarding children’s well-being. On the other hand, experts’ judgments about the academic impacts of COVID are usually based on changes in standardized test scores. Because parents failed to mention their childrens’ academic standing on standardized tests, the researchers concluded this data source was not as relevant to caretakers.

- Some caretakers perceived problems caused by COVID—but often among other children, not their own

Several caregivers in the study were aware of the damages caused by COVID among other children, specifically children of some other demographic group or in some other kind of school, rather than their own child. The researchers found that to be striking.

A sample of statements noting this observation included:

- A caregiver of a kindergartener said they thought learning loss would be worse for middle or high schoolers because they were “expected to learn more and more quickly.”

- A caregiver of a child living in a rural area said they thought learning loss would be worse in “certain areas, especially bigger cities.”

- One caregiver who worked at home and helped keep their child on task during remote learning felt learning loss was likely worse for families where caregivers had to be out of the house.

- Several caretakers believe that school and teacher expectations have been lowered

Researchers heard a mix of critical concerns regarding educational expectations. Collected caregiver statements ranged from “The bar got set so low for completing work and turning things in that the kids kind of got an idea—at least (my child) did, that she didn’t have to do as much” to “The curriculum overall has been really kind of dropped down to the lowest kind of denominator.”

Some caregivers believed, and continue to believe, that school and teacher expectations were lowered during COVID school closures, which may have had long-lasting effects on student motivation and academic experiences. Some of those concerned about lowered expectations believed that students were promoted to the next grade regardless of subject mastery, which could cause academic struggles later.

- Caretakers think children are resilient

Many caretakers cited the resilience of children. Regardless of the negative COVID-related experiences, caretakers thought students would ultimately “bounce back” or were already back on track. The researchers overwhelmingly heard the message that both children and adults are finally moving on.

What does this mean moving forward?

“It seems clear from our work that there really is a disconnect of sorts between experts’ concerns and caregivers’ concerns about student well-being and we uncovered several possible explanations for this gap,” said Rapaport. “One of them is that the standardized tests that experts use to highlight students’ learning loss as a result of COVID simply do not factor into most caregivers’ thinking the way that grades and subjective assessments of student well-being do.”

“The results have several implications for educators and parents,” said Polikoff. “We’re glad to be able to share the good news that most of the parents we interviewed perceive resiliency in their children, and that parent concerns about their children’s well-being do genuinely seem to be relatively low. But we think parents need clear and accurate information about how children are really doing, but with parents noting a lowering of expectations and an absence of external data from standardized tests, our results suggest that’s not really happening now.”

Both also stressed how the experiences of families during COVID varied tremendously and how the long echo of the pandemic continues to affect children differently. “Some of the kids are all right. Not all of them are,” concluded Polikoff.

The study was supported by the Peter G. Peterson Foundation Pandemic Policy Research Fund at the USC Schaeffer Center for Health Policy & Economics “The Kids Are All Right? What Parents Really Think About How COVID Affected Children” was authored by Polikoff, Rapaport and researchers Anna Saavedra and Daniel Silver.