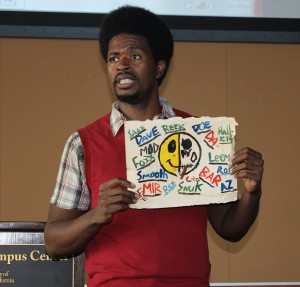

Amir Whitaker ME ’08, EdD ’11 stood before 200 urban high school students on March 15, and held up an old notebook cover scribbled with the initials of 18 of his closest friends from his youth in Plainfield, New Jersey.

Of the 18, he informed the audience, five have been shot, and eleven entered the prison system in adulthood. Three graduated from high school. He is the only one to have graduated college.

The tangible reminder of his adolescence has been a source of motivation for Whitaker, 28, founder and director of the one-year-old nonprofit Project Knucklehead. He recently visited USC for his Dreams Into Goals (DIG) Summit to show students from Lennox Academy, Stern Math and Science, Jackie Robinson, and Linda Marquez high schools how to turn their own dreams into goals.

“Even the most unmotivated students who are not interested in school have aspirations,” said Whitaker, who is currently working towards his fifth degree at the University Of Miami School Of Law.

“But their goals are very vague, what we call ‘dreams.’ So, the purpose of DIG is to tap into these dreams – to be a dentist, a doctor, an engineer – and turn them into goals with specific plans.”

Whitaker does not speak to these at-risk students from an ivory tower or a past of privilege. He speaks from his own experience.

With both parents incarcerated, Whitaker was raised by his grandparents in a 14-person home in which no one went to college. He didn’t see how education mattered because he didn’t know anyone who used it to succeed. By age 15, he had already begun following what he calls the ‘school-to-prison pipeline,’ and entered the juvenile justice system.

After being expelled from high school and placed in an alternative school, he met Mr. Johnson, a teacher who took Whitaker under his wing. “He took me to his house and gave me $20 to rake his leaves. He was the first person I was exposed to with a nice house and a structured family.”

With this and other positive mentor actions, Whitaker realized he could forge a different path for himself. He entered community college in order to “prove himself,” transferred to Rutgers University, and began working as a substitute teacher in his neighborhood.

“I was unable to motivate my students, and didn’t know what to do. When you’re not their real teacher, it’s even harder to tell them to do work,” he said. “I Googled ‘urban school motivation education’ and the first thing that came up was USC’s program.”

With support from the Donald Golder Memorial Scholarship, Whitaker earned a master’s and then an education doctorate in educational psychology at USC Rossier.

“Professor (Robert) Rueda was very influential. I always remember that in his class on student motivation he would say, ‘Most students have the same cognitive and mental processes despite their differences in achievement,’” Whitaker recalled. “’There is no achievement gap. There is only a motivation gap, and more than half of academic problems result from motivational issues.’

“I’ve had over 100 professors in the 12 years that I’ve been in higher education now, and he is definitely one of the best. The educational psychology expertise I gained at USC has really helped me understand the struggles schools face with student motivation.”

Whitaker said he infused motivation theory and research into his summit to address issues other intervention programs do not.

“Research shows that schools that suspend more students have lower test scores, and I remember being happy when I was suspended from school because I didn’t want to be in school anyway,” he said.

“Assigning extra work and tutoring are also interventions that won’t help if the student is not motivated to do the work in the first place. And calling home doesn’t work if the parent is really busy or has already given up.”

At the summit, college student volunteers work as mentors, sharing the traditions and culture of college life. They also help the teens reflect on their values and environments, and set specific measurable goals to change their behavior over the next month. Those goals or DIG Plans are then signed by students.

In the coming year, while continuing to work towards his law degree, Whitaker said he wants Project Knucklehead to empower at least 1,000 students around the country. He also hopes to coordinate monthly mentor visits at the students’ schools to ensure they are following their DIG Plans.

So far, it appears to be working. For 75 percent of the participants, the summit was the first time they stepped onto a college campus. One hundred percent of students who completed the summit reported that they were more motivated to stay in school, Whitaker said.

Whitaker, who also teaches law at a juvenile detention center in Florida, said the program is designed for those students most at risk for dropping out.

“We want the ‘knuckleheads’ like I was, who are not doing the work, who are disrupting class, who will likely drop out, and maybe even turn to a life of crime,” he said. “We want to inspire them to reach their true potential and become productive citizens.”

We are pleased to announce that Whitaker will be the 2013 masters ceremony commencement speaker on Friday, May 17th.