As an educational leader, how do you achieve economic equity for all students? That’s a question Lawrence Picus, PhD has explored through much of his career.

As part of our blog series on equity in education, the experts at USC Rossier are sharing their takes on the topic. (Check out our other posts on racial equity and gender equity.)

For Picus, equity is best understood when viewed through the lens of school finance.

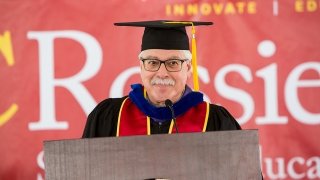

Picus is the Richard T. Cooper and Mary Catherine Cooper Chair in Public School Administration at USC Rossier. In addition to his career as a scholar, he edited the book, School Finance: A Policy Perspective, co-authored other works about school finance, and has consulted extensively on school finance issues in more than 20 states.

(Interested in equity in education? Learn more about our graduate programs.)

Here’s his take on economic equity in education.

What is economic equity in education?

Economic equity in education is the process of distributing an equal amount of money to students with equal efforts through taxpayers. “If taxpayers pay different rates of taxation for the same level of services and resources, that is unfair,” explained Picus.

Once taxes are equitably determined, the next, more challenging step is to allocate the funding. Schools measure success in part through student outcomes and performance (e.g., test scores and graduation rates), and use their public funding to help students achieve those outcomes.

However, some students may have specific needs that require additional resources to be successful. As a result, schools must figure out how to allocate their funds equitably to address different needs.

Additionally, the distribution of funding depends on the laws in individual states. California has its own set of mandates that may differ from those of, say, Arkansas.

Title 1: A federal solution to economic equity

Title 1 is part of the federal Elementary and Secondary Education Act, which seeks to improve the academic achievement of disadvantaged students. It provides government funding for schools with low-income children who may not have the same educational support and opportunities as middle or upper class children.

Title 1 funding can be used to improve a variety of resources including curriculum, counseling, school programs, and more. According to the Brookings Institution, to be eligible for school-wide funding, 40 percent of a school’s students must be eligible for free or reduced-price lunch. (There is some debate, however, over whether or not Title 1 is effective.)

Title 1 funding can affect the calculation of how resources are allocated in a given school. Additionally, all 50 states have programs that provide compensatory funding to students who are eligible for Title 1. State programs also offer support for a range of other student needs including English language instruction and special education.

How to evaluate your equity efforts

If you work in school finance, Picus suggests there are two measurements with which you can evaluate your use of funds: adequacy and equity. Adequacy refers to the amount you need to provide reasonable assurance that every student will succeed. Determining the number required to achieve adequacy will depend on the needs of the school’s students.

Then, if you figure out how much you need for every student, and can ensure fair tax efforts from their parents, you can distribute funds equitably.

Improving economic equity is a two-step process

Improving economic equity requires schools to investigate their resources in a two-step process:

- Schools should ensure that every student has the resources they need to achieve at high levels. Resources should cover all students, including those with additional needs that require special support.

- Schools need to ensure that resources are available to students per the laws of their state, regardless of their location.

For a clearer picture of how to distribute resources, it helps to understand two types of economic equity:

Horizontal equity - This is a scenario in which every student receives the same resources, regardless of need.

Vertical equity - This is a more dynamic approach to equity in which schools provide extra support for students who lack the resources of other students. For example, children who belong to a low-income family on food stamps face additional barriers to academic achievement, and can benefit from additional resources.

Both forms of equity are critical. It is important to ensure all children have the resources they need (vertical equity) and that all children with the same needs receive the same level of resources (horizontal equity).

How to distribute resources fairly

While the efforts of taxpayers and student outcomes are important, recognizing the different needs of students is a critical element of economic equity. Schools should determine how to make education accessible for everyone, knowing that circumstances may hinder students’ ability to perform at their best.

How should schools address student needs equitably? Picus suggests that a model of fair resource allocation can be built on three categories of students:

Students from low income families - students from families who need extra support due to financial challenges.

Non-English speakers - students who struggle to meet standards of academic achievement due to a language barrier.

Students with disabilities - students with special conditions that may interfere with their ability to learn. (Special education students at schools are required to receive more resources than any other type of student, although states have different rules about how those resources should be allocated.)

Economic equity and race

How race affects the allocation of school resources is a topic of considerable debate. While evidence shows that race likely plays a role in the learning outcomes of minoritized children, there is no federal law mandating that it must factor into school finance. Schools have to determine for themselves whether or not racial differences necessitate different resources, as well as the legal consequences of using race as a factor. (and if resources are available, how they should be used).

Economic equity at public vs. private schools

With the exception of some schools that receive Title 1 money, private schools in the United States do not receive taxpayer funds. But “resource allocation in general is likely pretty similar in private schools,” explained Picus. The data for these institutions is private, however, so it’s hard to describe allocation with absolute confidence.

Private schools are free from an obligation to taxpayers, which gives them more flexibility in how they apply their funding. But while student needs vary from school to school, private schools use resources to address them in similar ways.

However, the most exclusive private schools are not accessible to low income and even middle-class families, creating an equity “conflict” between individual property rights to spend your money as your choose, and the public’s right to equal treatment.

Graduate programs train leaders to address equity

Managing economic equity is a complex job. However, graduate programs can prepare educational leaders to allocate resources to meet the needs of individual children. As a student earning your doctoral degree, you learn to understand the difference between equal (giving all students the same level of resources) and equitable (students’ perceived needs).

Additionally, you receive expert guidance on the various ways you might allocate resources. Should money go to your school? Should the family of students in need receive funds? Is additional tutoring an effective use of resources? A comprehensive training in equity practices can make graduate programs in education a smart move.